8/14/1881 – 6/1972

“KNOWN BUT TO GOD…”–“Here rests in honored glory an American soldier, known but to God.” So reads the inscription on the tomb of the unknown soldier buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Kirke L. Simpson of the Associated Press won the Pulitzer Prize in 1922 for his story that day. It started this way, and it belongs in any history of the time:

Under the wide and starry skies of his own homeland,

America’s unknown dead from France sleeps tonight, a

soldier home from the wars.

Alone he lies in the narrow cell of white stone that

guards his body; but his soul has entered into the spirit

that is America.

Wherever liberty is held close to men’s hearts, the honor

and the glory and the pledge of high endeavor poured out

over this nameless one of fame will be told and sung by

Americans of all time…”

_________________________________________________________

The following was taken from the draft of an article written by Paul K. Lee. It was marked up with directions for layout for publication in a newspaper. I assume it was published, but the draft does not contain any date or other identifying data. It is an excellent summary of Kirke L. Simpson’s career with the Associated Press and his accomplishments.

Let’s have a visit with —

Kirke L. Simpson

Who was an AP man in San Francisco and Washington for 37 years. His 1921 story on burial of the Unknown Soldier won the first AP byline and the first Pulitzer Prize ever awarded a news service man; still appears in journalism textbooks. For many years he was AP¡¯s Washington political columnist. He broke the news of Teddy Roosevelt¡¯s Bull Moose campaign, and made smoke-filled room a potent political phrase. He has been retired 25 years and at age 88 still has “some reading to do.”

By PAUL K. LEE

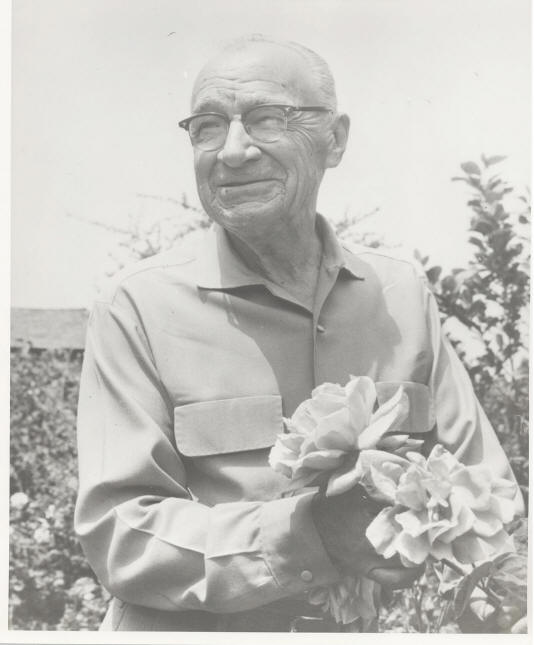

Retired AP man Kirke L. Simpson and his wife Irene live peacefully in their seven-room white stucco home at 17675 Vista Ave., Los Gatos, Calif. 95030, about 90 minutes south of San Francisco by car. Though Los Gatos is their mailing address, their home is located in beautiful Monte Sereno, and from this snug spot they observe today’s noisy and bustling world.

Simpson’s hair is thinning and gray, but his handshake is firm and his step sure. He exudes a quiet contentment with life as he finds it there, amid greenery and flowers. He knows about the troubles elsewhere; but, trained all his life to be objective and impartial, he hands down no judgments or pronouncements. Reading is his only hobby. He prefers magazines (especially likes roundup stories of events after the dust has blown away). But he reads newspapers, too, and carefully follows the news on radio and TV.

Simpson looks forward to his 89th birthday next Aug. 14. “I should be good for a few more years,” he says. “I still have some reading to do.”

***

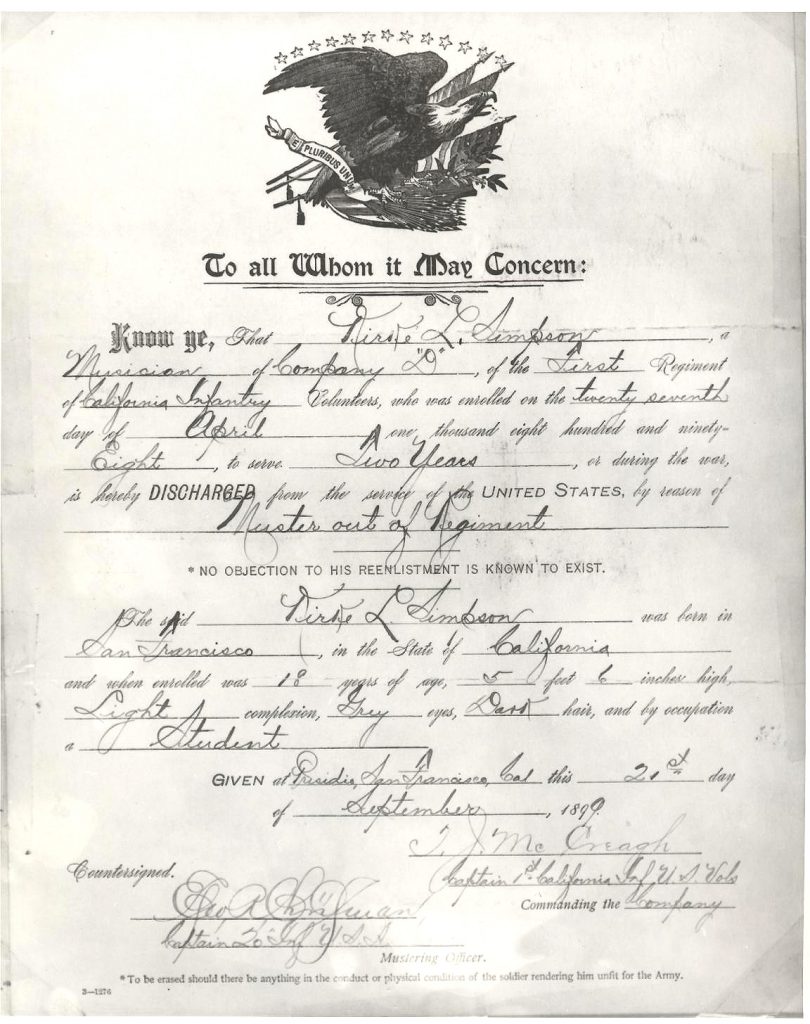

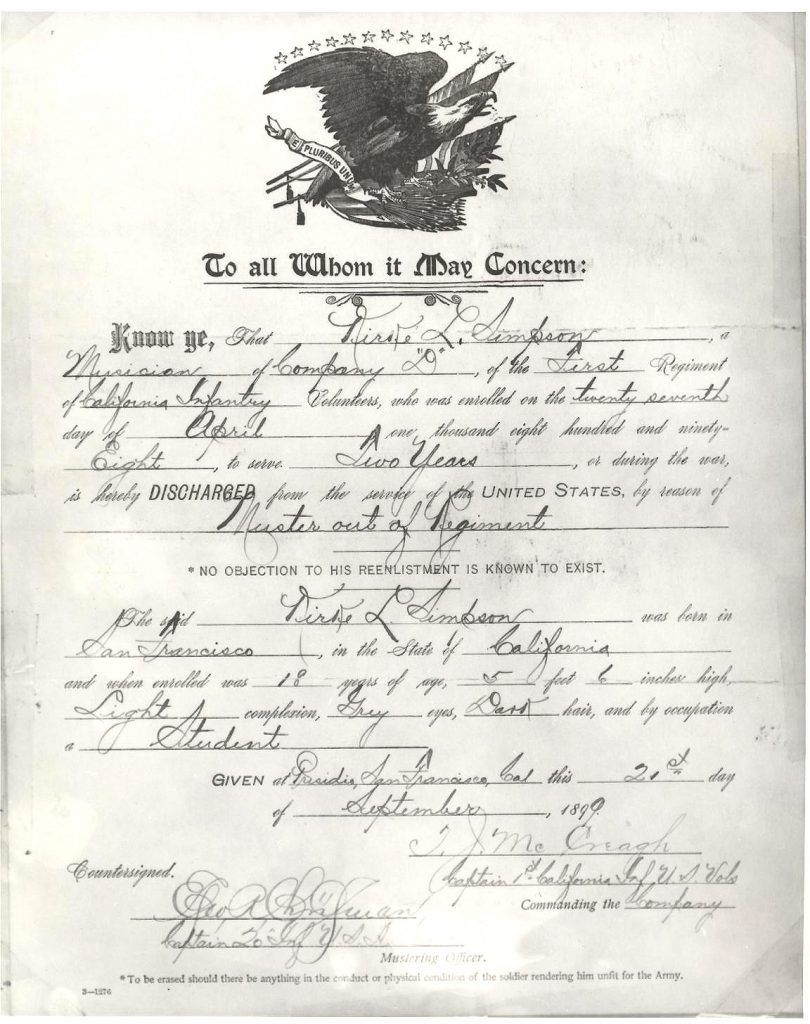

Kirke Larue Simpson was born in San Francisco, son of an attorney, and grew up there with four brothers and four sisters. When the Spanish-American War broke out he took to uniform, age 17. As a bugler with Co, D, 1st Calif. Vol. Inf., He took part in capture of Manila (1898) but couldn’t bring himself to shoot at the one Spaniard who came within pistol range. For a short while after the war, Simpson studied at the University of California in Berkeley, then decided to enter newspaperdom.

He had two older brothers on the San Francisco Chronicle. Brother Ernest was city editor. Brother Lynn was telegraph editor. Lynn also had a sideline: putting together a daily news report for the Tonopah (Nev.) Daily Sun. Another brother, Francis, was an engineer in the Tonopah gold mines. Kirke broke in on the Oakland Tribune, staying just long enough to see how news is processed. Then, with help of brothers Lynn and Francis, he got a job on the Tonopah Daily Sun. He had signed up as a cub reporter, but when he got there he found himself editor of the paper.

“My predecessor left Tonopah on the same train that brought me in,” Simpson recalls, “so I had to handle the news, editorials and makeup, passing it on to a noisy flatbed press driven by a gasoline motor.” Tonopah still had some rough residents in those days, and an editor ran risks of having his head sliced off and handed to him. In 1904 someone did plant a package of lighted dynamite in Simpson’s office, but fortunately the fuse fizzled out.

***

In 1906, when the Great Earthquake struck San Francisco, brother Lynn sent a flood of quake news to his Tonopah client ¨C so much that Kirke couldn’t squeeze half of it into the paper, but Tonopah residents were hungry for it and as they stood on a throng outside the printing plant Simpson read aloud each telegram as it arrived. { The Daily Sun was Tonopah’s afternoon paper. Its competitor was the morning Tonopah Bonanza. Neither was an AP member, though the Bonanza joined AP late that year, receiving 1,000 words nightly by overhead telegraph and paying an assessment of $33 weekly.}

A few days after the earthquake, Simpson went back home to take a look. “They had stopped the fire at Van Ness Avenue, one of the few wide streets, by blowing up the buildings,” Simpson remembered. “I was most impressed by the acres and acres of brick chimneys standing alone where homes had been.” The death toll was 452, the property loss $350 million. But Simpson learned all his relatives had escaped harm.

***

In 1908, when Simpson was 27, he applied for a job at San Francisco AP and got it ( on a probationary basis that lasted five years), “though I didn’t have an extensive education.” “By today’s standards the AP wouldn’t have hired me,” he says. “I don’t believe I could have passed a present-day writing test.” But he was ambitious to learn.

Then, as now, chances were overwhelming that before long an ambitious young AP man would show up at a larger AP bureau during vacation. Late in 1910 Kirke Simpson visited the Washington bureau, and the effect was immediate. The WX bureau chief, John Palmer Gavit, told Simpson that Theodore Roosevelt soon would leave Washington on a cross-country lecture tour. He arranged for Simpson to accompany him ¨C and Simpson was the only reporter on the train. The tour ended at Helena, Mont. There Teddy Roosevelt told Simpson about his plan to run for president again in 1912. As a result, Simpson scooped the world with his advance story on what turned out to be the Bull Moose campaign.

***

Simpson returned to the San Francisco bureau, and remained there until he was summoned to Washington in 1913. It was at this point that Simpson first became a “regular” AP staffer. The following year he was dispatched from WX to Mexico in connection with the Pancho Villa uprising, and when he got back to Washington he was assigned to cover the State, War and Navy departments. Meanwhile, Franklin D. Roosevelt had become assistant secretary of the Navy. FDR and KLS formed a truly close friendship that lasted until FDR¡¯s death.

In 1920 Simpson covered his first national political conventions ¨C the Republican in Chicago and the Democratic in San Francisco. One of his leads from Chicago said, “Harding of Ohio was chosen by a group of men in a smoke-filled room early today (June 12) as Republican candidate for president.” Ever since, smoke-filled room has been a commonplace and meaningful expression.

***

Later in 1920 Simpson was assigned to observe from a blimp the America’s Cup yacht races off Long Island ¨C and the blimp came down in the waters of Jamaica Bay. Simpson¡¯s moving AP story of this experience bore no name, of course. But the New York Times added to it a forward disclosing the writer’s name. It was the nearest to a byline that any AP man had ever had, and it was an omen for the future.

***

In 1921 Kirke Simpson had been an AP man for 13 years and, like other AP men, was virtually unknown for lack of mention. But that year he broke the ice for all concerned with his stories on return and burial of the Unknown Soldier of World War 1. Simpson has a ready explanation for why he got this historic assignment: “I was covering the War Department, and it was on my beat.” And the stories, he says, were mostly a matter of just writing “line by line.” The first story, the one that caught everybody’s eye, began:

” WASHINGTON, Nov. 9 ¨C (By The Associated Press) ¨C A plain Soldier, unknown but weighted with honors as perhaps no American before him because he died for the flag in France, lay tonight in a place where only martyred Presidents Lincoln, Garfield and McKinley have slept in death!”

So inspired, so electrifying was Simpson’s prose in context of the time that telegraph editors across the country felt it as a personal thing. It brought tears to some eyes, and messages to AP headquarters asking who wrote it. Setting aside an unwritten AP rule 73 years old, the AP general manager put a special note of the wires, identifying the writer and giving permission to use his name. Over the next two days, culminating with the Armistice Day burial in Arlington, there were seven stories in all. Only one, which paraphrased Robert Louis Stevenson’s Requiem, was planned. The others came “right off the cuff.” As Simpson puts it. Mrs. Simpson retains a faded scrapbook containing the original wire note.

“Melville Stone was the general manager then, “Simpson said with an almost inaudible chuckle. “He was a rather austere fellow. You didn’t get very close to him.”

***

Having been showered with acclaim and awarded the Pulitzer Prize, Kirke Simpson went right on reporting the news of his Washington beat ¨C anonymously. Eleven years later the late Kent Cooper, then AP general manager, remarked how calmly Simpson stood up under his sudden fame: “He did not let it turn his head or convince him that he was the best reporter on earth.”

***

Simpson recalls: ” I missed a very good story later. I was on vacation in London when Lindbergh flew to Paris on May 21, 1927. They tried to get hold of me to ride the ship back with him, but I couldn’t be found. I was glad of it; I wanted to continue seeing England.”

***

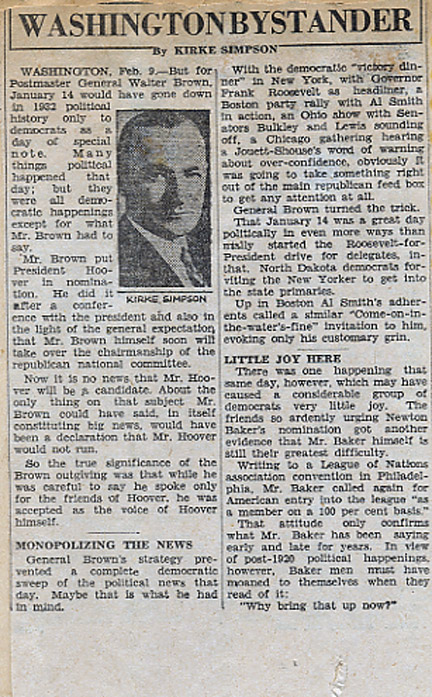

In 1928 Simpson began writing his daily column, The Washington Bystander, and for the next 17 years, until he retired in 1945, nearly everything he wrote was bylined, thanks to a new policy established by Keith Cooper. In 1937 the late Washington bureau chief Milo M. Thompson told KC what KC already knew: that Simpson was of inestimable value to the Washington bureau; that “He is not only a good reporter, but also extremely valuable for his contacts, for his fund of background information, for his inspiration to new men, and for his interpretation of political news.”

For the first 11 years, Simpson’s column dealt with national politics, but in 1939 it was converted largely to interpretation of events in World War II. Simpson confesses now that he didn’t enjoy being a columnist ¨C “I got awfully tired of it” — mostly because its explanatory and background matter was published too far behind the news breaks to which it applied; in other words, kept him too far from the firing line. But he enjoyed acquaintance with the notables of his time.

As a man who has witnessed so much important history in the making, has Simpson ever thought of writing his memoirs? “No,” he said firmly, “I never felt any urge about it. I always preferred straight news.”

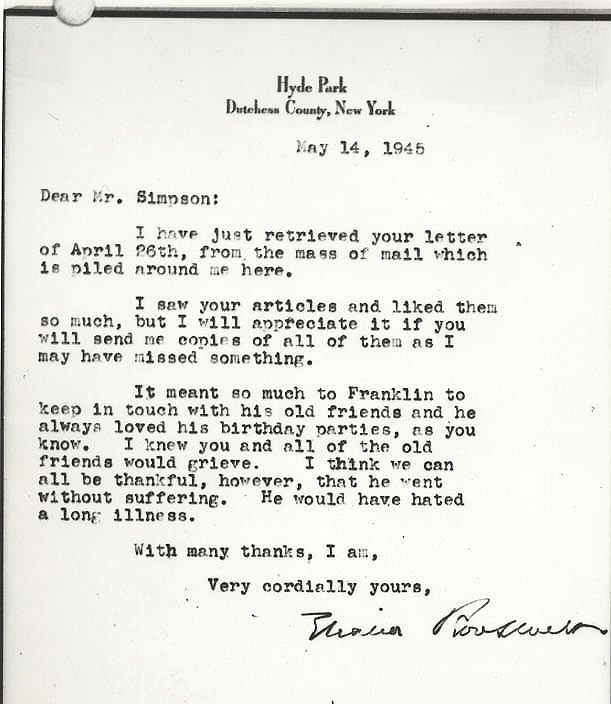

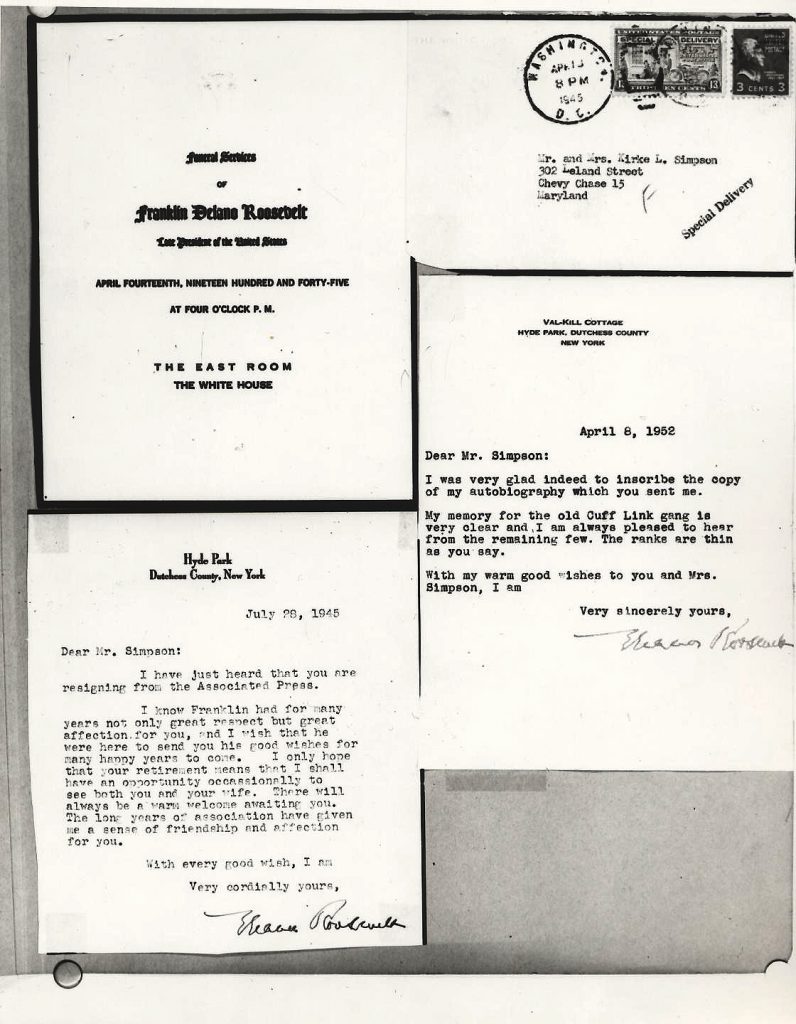

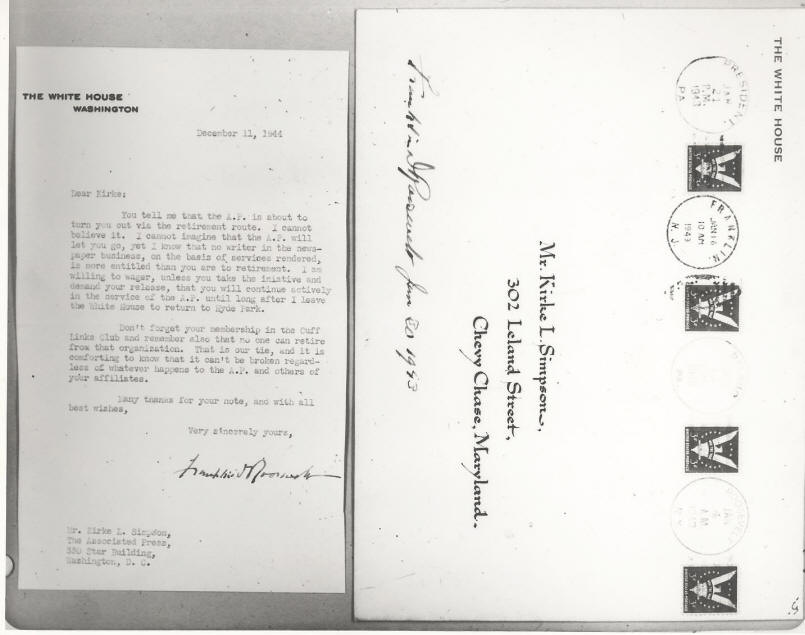

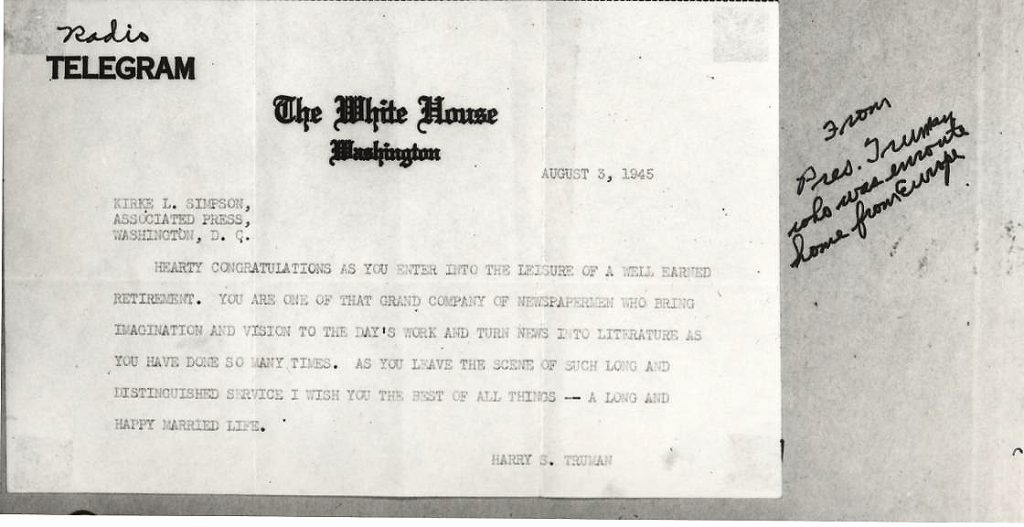

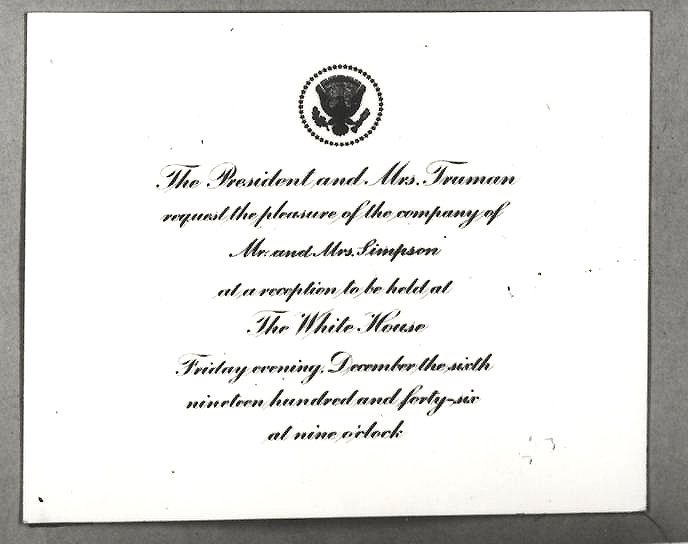

At the end of February, 2005, Helen Beedle sent out another thick packet of Uncle Lynn’s family history files. Within the packet were these letters from Eleanor Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman to Kirke L. Simpson, plus a couple of other photographs relating to Kirke:

The following is a poem written by Kirke L. Simpson, that was published in the Overland Monthly in 1908, about the rebuilding of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake.

The City That Is To Be

By Kirke Simpson

“The City That Was”, they dubbed it,

As they mourned o’er the smoldering heap,

They were men who had known it in halcyon days,

And they told of its passing in sorrowing phrase,

Recounted its sins and its glad, wild ways,

And sighed for the things that had been.

“The City That Is”, we called it,

And we worked with brain and brawn.

We hewed to the line as we built anew,

Laying our timbers firm and true,

And our pride soared high as each building grew

Where a tangled wreck had been.

The good St. Francis heard the words,

And he judged each man where he stood.

He watched as we toiled through the hurrying days,

And he saw that our work was good.

Then he said, “My Children, ye both are right,

Though but past and present ye see.

My city shall rise, both good and great,

To keep its post by the Western gate;

And ye both shall share in the days that wait,

The City That is To Be.”

Overland Monthly, p. 294, Vol. 72, Jan ¨C June 1908 Co51 098 Calif St. Library

_________________________________________________

Additional Notes on Kirke L Simpson:

Married Ella May Field in 1945,

Second marriage to Irene Lisherneff in 1953.