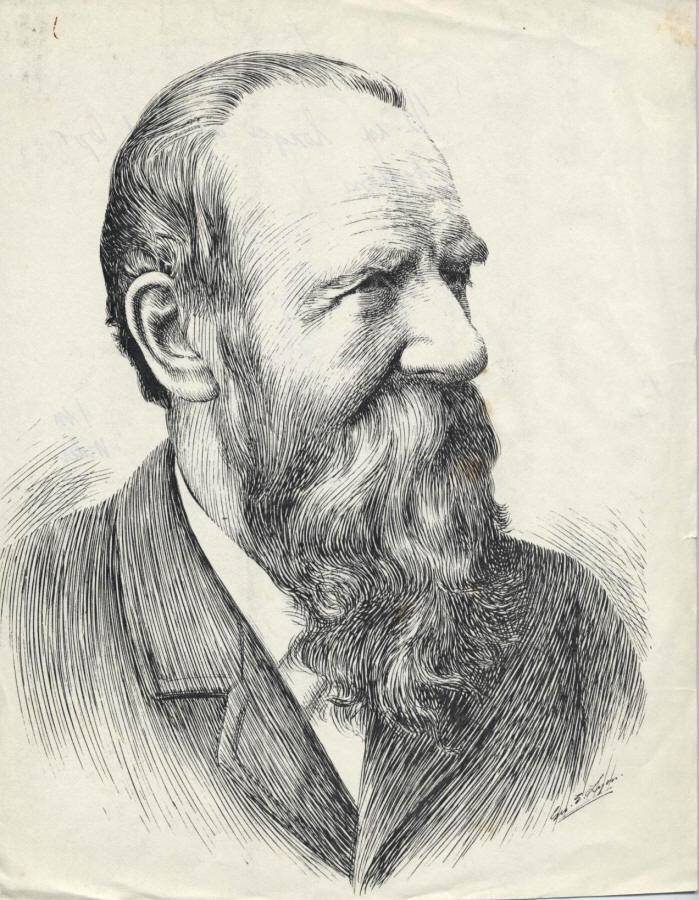

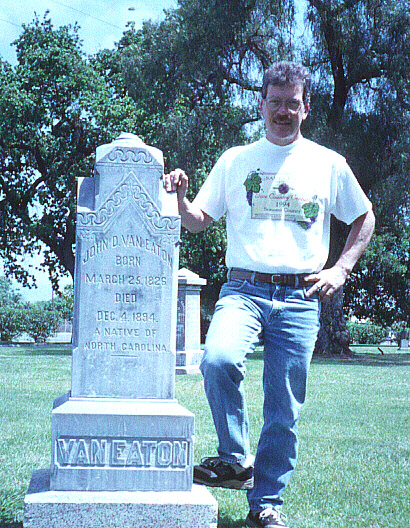

3/28/1829 – 12/2/1884

John Dick Van Eaton was born in 1824/5 in Mocksville, NC; attended Emory and Henry College in VA for almost four years, when in 1849, gold “fever” struck, and he headed west to join a wagon train to California. When the group reached Carson City, John sold his horse and hiked over the Sierra Nevada Mountains, eventually arriving at the gold camp of “Hangtown” (later called Placerville). There he staked a claim and must have had some luck at mining, as he is said to have sent $5,000 to his father to tide him over during the Civil War. He soon took the job of Deputy Sheriff, serving for 12 years, as it was said, “right in the middle of the wildest period of the wildest county in California’s history.” There were hold-ups of stage coaches carrying gold from the mines, murders over disputed claims, women, etc., and lawless characters disrupting the town and countryside.

From The Argent Castle, The Newsletter of the Clan MacCallum/Malcolm Society, date recent but unknown.

“From James Tillotson (son of Jane Stuart), we now know that John Guthrie’s sister, Jane Stuart McCallum, also came to Placerville, probably to nurse the ill brothers. She was married there January 1, 1862, to the “handsome, gun-toting deputy sheriff,” John Dick Van Eaton.

One of the famous crimes Van Eaton helped solve was the “Great Bullion Bend Robbery” in June, 1864. A group of Southern sympathizers, hoping to secure some much-needed money for the Confederacy, held up two stages at Bullion Bend, took their gold and made off. Later, after a part of the group had been caught, the sheriff put Van Eaton in the jail with them to pose as an ardent supporter of the Confederacy and find out the names of the other robbers. The ruse worked, and after a gun battle at the house where they were holed up, they were all jailed.

John Dick and Jane Stuart McCallum had four children: Harriet Ellen, born 1863; John D. born 1864/5; Jane Stuart, born 1866 (died in infancy); and Elizabeth Belle, born 1868, and later married Lynn Carroll Simpson.

John Dick Van Eaten moved to San Jose, CA, later in his life.

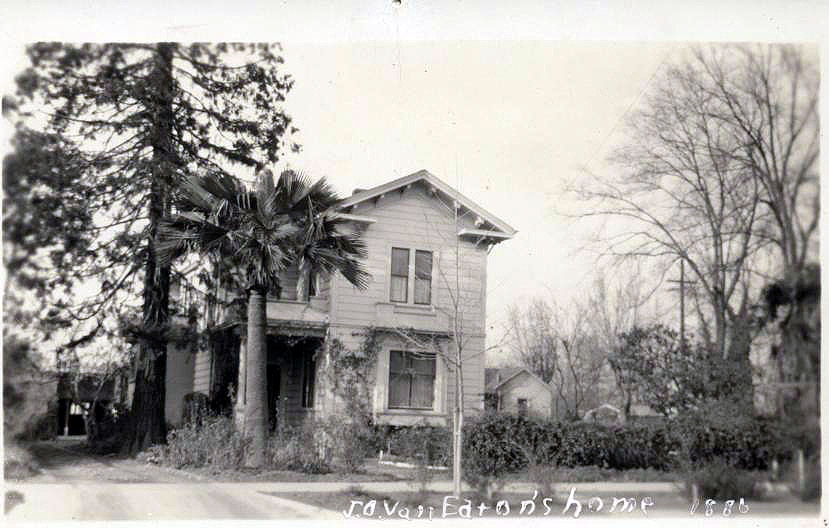

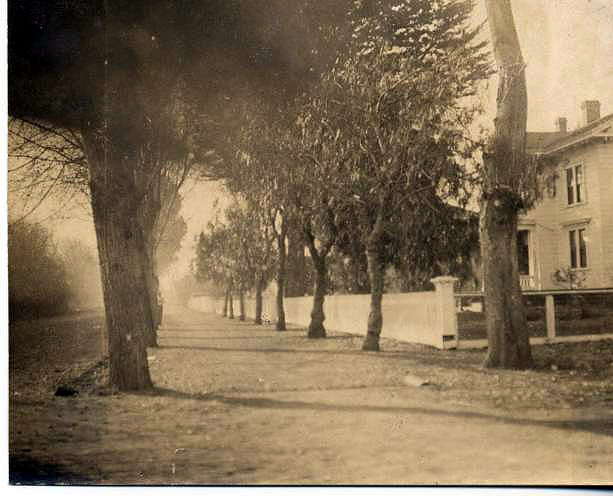

Pictures of the house at 1021 University Avenue, that was originally owned by John Dick Van Eaton, and later by Lynn Carroll & Elizabeth Belle (Mammee) Simpson. Carol Enid (Simpson) Beedle was born in this house.

Same home in 1886.

The following is the first eight pages of a 21 page document written by Henry Bailey sometime after Fall of 1953. The eight pages included here cover family members of interest to this website, namely John Dick Van Eaton (Henry’s Grandfather) and his children, Harriette Ellen Bailey, John V. Van Eaton, and Belle Simpson(Carol E. Beedle’s mother). The remaining pages cover the Bainbridges, Baileys, and Tillotson families are are not reproduced here. The portion pertaining to John Dick Van Eaton is excerpted below.

A History of the Bailey Family

By Henry Bailey

It has always seemed rather odd that a Dutch family should have settled in the western part of North Carolina prior to the revolution, but my curiosity has never led me to trace the Van Eaton family further back than John V. Van Eaton, of Farrington, David County. Owner of a plantation, he fought at Cowpens and Kings Mountain, but his name will not be found on the roster of any military organization of the Revolution. Practically all the rosters of the North Carolina forces were made from pension claims, and John spurned any pension. “It was only my duty to fight for my country,” he doughtily said.

The Van Eatons naturally married the descendants of the Scotch Covenanters who had settled Western North Carolina, and names like McNeal and McAllister abound in the family genealogy. At times, they went further afield for brides, one bringing home the daughter of the Adjutant General of South Carolina, when that great state made its first attempt at secession. (Somewhere along the line, I’ve lost the name.)

My grandfather, John D. Van Eaton, was born on the family plantation in 1826, the oldest of twelve children, ten boys and two girls. His father was also noted for his humane treatment of his slaves. John grew up with all the advantages that accrued to the son of a well-to-do Southern gentleman. He was a student at Henry College, at Emory, Virginia, for almost four years, but with the other members of the senior class quit the school in protest over the expulsion of one member. As this was in the spring of 1849, when the Gold Rush was at its height, there may have been some connection. At any rate, John returned home, secured a belt full of gold from his father, mounted his trusty mare, and started on the long trek to California.

At Independence, Missouri, he joined up with a wagon train, and the trip to California was not without its exciting moments. One bachelor member of the train coveted not only a fellow member’s wife, but also his wagon, and somewhere in what is now Wyoming, the bachelor did away with the husband. With the husband missing, the finger of suspicion pointed at the bachelor, and the leader of the train named a jury, a prosecutor and a defense attorney. Grandfather sat on the jury that convicted the man, built the gallows and hanged the miscreant. The body was left hanging on that windswept plateau. “The loneliest sight that I ever remember,” said Grandfather in telling this story, “was that body ‘swaying in the wind.”

Grandfather must have been a little reckless with his gold, for by the time he reached Carson City, he was so broke that he sold his trusty mare, put his pack on his back and hiked across the Sierra Nevada mountains on foot. Arriving in the then hell- roaring camp of Hangtown, now the quiet and quaint mountain village of Placerville, he staked out a claim and in no time at all was a hard rock miner.

Two of the town’s bad men, seeing this promising claim being, worked by a quiet, soft- spoken courteous youngster, decided they would take over, and one day, returning from his midday meal, Grandfather found the two holed up in the tunnel he had run into the side of the mountain.

“Come out,” he said, “or I’ll throw you out.” They replied with some jeering remark, and Grandfather, a big, powerful man, strode down the tunnel, knocked their heads together, and threw them out on the dump.

His reputation was made. “Just the man for deputy sheriff,” everyone agreed, and for the next twelve years, Grandfather was right in the middle of the wildest period of the wildest county in California’s history. Gold by the millions was being taken out of “them thar hills”; murder for that gold was a common occurrence; stages, carrying the gold were being held up constantly, outlaw bands roamed the country; and of course there were always a few roistering characters trying to shoot up the town.

Grandfather, along with Undersheriff James Hume, afterward head of the Wells Fargo detective service, was in the posse that wiped out the Rivers band. Engaging in a gun battle with Rivers, Grandfather came out second best, being badly wounded, but he stayed in the fight until Rivers was killed and the rest of the band either killed or captured.

All the gold mined in California in those days was carried from the goldfields to the banks in Sacramento or San Francisco on horse drawn stages under the supervision of the Wells Fargo Express Company, and holding up stages and making off with the gold dust or the gold bars was the favorite pastime of outlaws.

Probably the most famous crime that Grandfather solved was the one of which he was least proud, the great Bullion Bend robbery. In June, 1864, a group of Southern sympathizers, knowing the confederacy was desperate for gold, devised a plan to hold up the stages a few miles west of Placerville, at a spot still known as Bullion Bend.

According to the official history of El Dorado County, housed in the Bancroft Library at the University of California, the robbery was carried out in true Wild West fashion, but with a few added touches. As the first stage rounded the bend, the masked men stepped out, stopped the stage, disarmed the messenger, and unloaded the gold. No sooner had this task been completed than the second stage rolled around the bend and the performance was repeated. The passengers were assured none would be harmed, but the leader of the band gave such a stirring speech on the poverty of the Confederacy that the passengers were moved to deposit their gold and valuables with him. He gave the stage driver a receipt both for the gold and the valuables, and with a courteous farewell, the robbers took off.

In leaving, the band split into two groups, and as soon as news of the hold-up was carried back to Hangtown, two posses started in hot pursuit. The smaller group was picked up in short order and jailed and the other group was traced by three deputies to Eleven Mile House, where they had holed up. As Grandfather had the fastest horse, he tore back to Hangtown for reinforcements. The other two deputies were supposed to watch the tavern, but one became impatient, walked into the building and up to the room where the robbers were resting, threw open the door and cried, “Surrender in the name of the Law.” Those were his last words. A blast of gunfire cit him down, the robbers grabbed their loot, tore out of the tavern, mounted their horses and were off, taking a few shots at the other deputy hiding behind a tree.

By the time the new posse arrived, the band was clear out of the country, leaving without a trace. As Grandfather was a stranger to the members of the band taken prisoner, the sheriff threw him into the same cell as a dangerous secessionist. With his soft Carolina accent, he had little trouble in convincing his fellow prisoners that he was an ardent supporter of the Confederacy, and in short order had the names of the other plotters.

In company with Undersheriff Hume, he journeyed to Santa Clara County and with the cooperation of the sheriff’s office of that County, soon had the band surrounded in a ranch house near New Almaden. The gang was planning to hold up the quicksilver mine. A real Wild West battle ensued, with lots of gunfire but no casualties. The marksmanship on both sides was poor. One member of the band, Clendennin by name, threw open the door of the ranch house and stalked out with a pistol in either hand. When he had emptied both guns at the posse, he threw them down, and raised his hands in surrender, untouched but with twenty-four bullet holes in his clothing.

Justice was a little odd in those days, also. The entire band gave up, and were carted back to Hangtown, and thrown into jail. Warrants were then issued for their arrest, and they were brought to trial. One was convicted of murder, one was given twenty years in the penitentiary, and the rest went scot free, returning to Santa Clara County to become pillars of the community.

In the meantime, Grandfather had married Jane McCallum, and a baby, Harriet Ellen Van Eaton, had been born. Grandfather returned from his trip to the Santa Clara Valley, raving about its beauty and fertility, and I can imagine that Jane said something like this: “John, you are not as young as you were when you took this job. It’s time you quit roaring around the county, throwing malefactors into jail. You should settle down and you’ll never do it in El Dorado County. Let’s move to Santa Clara.”

The family did move to the Santa Clara Valley, and Grandfather became a farmer and a teamster, hauling sand and gravel about the same as the operator of a single truck today. It must have been a little tedious after the excitement of the sheriff’s office and the McCallums looked down their aristocratic noses at him, as little better than a common laborer. It was hard work, but he kept at it, and did fairly well for himself, built a good home in one of the better sections, between San Jose and Santa Clara and gave his children a good education.

It’s almost impossible for the fourth and fifth generations to realize how much hard manual labor there was in the world a century or even a half century ago. Let me describe how my grandfather spent a typical working day. Up at the crack of dawn, or well before that in the wintertime; out to feed, water, curry and harness the team; then clean out the stable; in to breakfast; out to hook up the team to the wagon and off for a ten or eleven hour day. The wagon had front wheels three and a half feet in diameter, rear wheels, four and a half feet, big so that two horses could pull two yards of gravel, five thousand, five hundred and sixty pounds out of the creek bed and over the dirt roads. The floor of the wagon was made of two by four planks, rounded on the rear end, the sides of two by twelves.

All my grandfather had to do was to drive to the bed of Coyote Creek, and shovelful by shoveful, raise the five thousand, five hundred and sixty pounds of gravel into the bed of the wagon, climb back into the seat, little more than a plain board set on two leaf springs, with no rest for his tired back, haul the load to its destination and dump it. That part was relatively easy. He pried up one side and then one by one turned the two by fours on edge and let the gravel run out. And remember he did this ten or twelve hours a day, six days a week.

He must have been quite an intelligent citizen, without most of the prejudices we are accustomed to associate with Southerners. Although a staunch Democrat, he voted for A. Lincoln in 1864, and he joined the Methodist Church in College Park, as distinguished from the Southern Methodist, there being no church of the latter denomination conveniently located. To those of you to whom the Civil War is just a part of history, it must be difficult to realize how bitter the feeling, how deep the division long after the war was over. Grandfather Bailey’s family turned Presbyterian when they moved to Long Beach, twenty years after the war was over, rather than join the Methodist Church, sturdy Methodists though they were, and as late as 1910, Sue Ramsay, one of my girl friends, went stamping out of a church party because the pianist started playing “Marching through Georgia” while we were playing “Musical Chairs.”

Three truly remarkable children were born of this marriage, Harriet Ellen, John V. and Elizabeth better known as Belle. Harriet is no doubt responsible for that high IQ of which my brother Phil and my son Bill are so inordinately and not so secretly proud. She could read at three years, graduated from the San Jose Normal at sixteen, and was a full fledged teacher before she was seventeen, teaching all eight grades in a small elementary school.

She was a most remarkable woman in many other ways with a marvelous singing and speaking voice. It is indeed a tragedy that her children inherited only the volume and none of the music of her voice. With all the work and all the cares of a family in the house, she took time to read for an hour to my brother Roy and me every night. A great admirer of Dickens, and she made those characters come alive. We wept for Dora, raged at Scrooge, laughed with Sam Weller, and shivered with Oliver Twist. Of course, the printed page had an unholy fascination for her. If she couldn’t read Dickens, she devoured last month’s newspaper with almost equal fervor.

She had a most equable temperament. With all the sound and fury of seven lively children, she never lost her temper nor raised her voice. The only time I can remember her needling my father was about six months after he sold the forty acres just outside Long Beach for $5000. Three months after he closed the deal, the man across the road sold his forty acres for $10,000., and three months later, the neighbor of the other side sold his forty for $15,000. “I think,” she told my father, “you sold a little too soon.”

She did, however, have one cruel and really inhuman punishment for the older boys. Personally she never laid a hand on any of her children, but when her patience was finally exhausted by the boys’ shenanigans, she would say, “I will have your father attend to you when he gets home.”

During the rest of the day, the deportment of all three was beyond reproach, two because they feared they might be included, and one under indictment, in the vain hope she might relent. For all her easy going attitude, she never did, and when my father walked in the door sho would say, “Walter, I wish you would whip Hal.” At least it seems looking back over the years that my name was most frequently mentioned, but more of this later.

My father never hesitated but marched the culprit out to the woodshed, whaled him soundly, and only when he returned to the house did he ask, “What did he do?”

She was the fastest worker I ever knew, perhaps because she had so much to do. When my father was principal of the high school at Julian, in San Diego County, there were six children, ranging in age from six months to twelve years. Water was hoisted out of a well with a bucket; food was cooked on a wood stove; the house was heated with a fireplace in the front room. Light came from coal oil lamps, and wonder of wonders, we had a hand operated washing machine.

Although we lived five miles from the school and left each morning about 7:30, my father saw to it that everything possible was done to ease my mother’s load. Not only did we feed and water and harness the horses, feed the hogs, milk the cows (the chickens fed themselves), we filled the lamps, cleaned the chimneys, loaded the woodboxes and brought in two buckets of water. And on two or three mornings a week, I was delegated to operate the washing machine. A great improvement over the wash board (a corrugated piece of galvanized iron in a wooden frame. You rubbed the clothes up and down this board to get the dirt out. Just one step ahead of beating them on a rock.) The agitator was activated by a handle about two feet long, attached to a set of gears. You moved the handle in a semicircle over the top of the machine, and the gears whirled the agitator. One lot of clothes was put to soak in the machine the night before and a couple more in galvanized wash tubs. The wash room was an open shed, and on many a winter morning, I broke the ice in the washing machine before I could start it. No nonsense about hot water either. There wasn’t any.

Then my brother and I did the supper dishes every night. (Like practically everyone in America, we called the three meals, breakfast, dinner and supper.) Roy washed with the dishpan on the stove to keep the water hot. One lot served for all the dishes and the pots and pans. I scaled the dishes with the water from the tea kettle and dried. I can well remember out favorite topic of discussion. How old our sisters would be before we could wish the job off on them.

With all this assistance, my mother had a tremendous amount of work to do. After my father got the fires started in the morning, she dashed out to get breakfast. And what breakfasts. First fruit, and she put this all up herself, jar after jar after jar, then hot cereal. That is one item of food which hasn’t changed much in the last fifty years. We had Quaker Oats and Cream of Wheat, but we also had on other item, graham much, a miserable slimy dish. Then eggs or sausage (my father made the best sausage I ever ate) and hot biscuits three hundred and sixty-five days out of the year and three hundred and sixty-six on leap year, we had hot biscuits for breakfast. And with jam, or jelly, jams and jellies that she also put up glass after glas after glass.

Before we were off to school, there were three lunches to be put up. Then the breakfast dishes to do, the beds to be made, and clothes to hang out, and if perchance I had not time to rinse and blue the clothes, water to pull out of the well, bucket after bucket after bucket. Then the ironing, no small task. It was really hot work, even though a great step forward had been made, a removable handle. The old fashioned iron was all iron, handle and all. It was heated on the wood stove, and by the time the base was hot enough to iron, the handle was too hot to hold. Then some ingenious individual brought out an iron with the removable wooden handle. You heated the iron on the stove as before, then latched the handle on to it. But ironing was still a hot job. Ironing damp clothes, the iron did not stay hot long, so the ironer had to stand close to the stove. No time to lose in changing irons.

Bread baking was a task twice a week, on Wednesdays and Saturdays. The job started the night before, when the bread was “set”. The next day, the dough was worked into loaves and rolls, and allowed to rise. When it had reached the proper height, it was baked, and we had hot rolls, delicious ones too, on Wednesday and Saturday nights.

On of the reasons for baking Saturday night was that the roaring hot fire served two purposes. It baked the bread and heated the water for Saturday night baths. Showers were naturally unheard of but we never missed the weekly ritual even when we went swimming every day during the summer. All the largest kettles were filled with water and put on the stove to heat. The galvanized wash tub was pressed into service as a bathtub, and beginning with the smallest youngster, one by one we filed into the kitchen and were soundly scrubbed. Of course there was a considerable interlude between baths. First hot water was poured in, then cold. Next a dash to the well for more water to fill the kettles, and again to fill the buckets. Although the wood stove kept the kitchen steaming hot even in cold weather it could not heat up the water as fast as my mother could bathe one of the children. There was always plenty of time to carry the tub outside and empty it before the next lot of bathwater was ready.

After that busy Saturday night, I rather imagine that my mother really enjoyed Sunday. Although we had the cows to milk, the hogs to care for, the horses to feed, water and harness, we did get up an hour later, there were not lunches to put up. And the whole family except my mother and baby climbed into the spring wagon and were off to Sunday School and church. Peace and quiet descended on the household for about four hours, as we drove five miles for church services.

Of course, she had to cook a big Sunday dinner, and have it practically on the table by the time we reached home but then she was through for the day. The men folk, meaning my father, my brother Roy and myself – I never can remember fly brother Les doing any house work, or in fact any work he could avoid – always cleaned up and on Sunday night we had bread and milk for dinner. So you can see that she really had only a six and half day week.

Truly a remarkable woman; so near sighted she could see nothing without her glasses; so absent minded she would push them up on her forehead and wonder where they were; never a harsh word nor an unkind comment; with a tremendous capacity for enjoying life.

Her brother, my Uncle John, was also an unforgettable character, but in a greatly different way. The body of a Greek god, the face of a Roman senator, the manners of a Chesterfield, a personality that could “win friends and influence people”, a resonant baritone voice, and when he turned his gaze on the opposite sex, which he often did, they practically swooned.

I can strongly recommend his technique to all uncles. The summer my sister Margaret was born, we all went to San Francisco, and stayed with Aunt Belle, Mother’s sister, and Uncle Lynn. San Francisco was then the tenth largest city in the country, and we came from a very small village. Uncle Lynn got us tickets for Barnum and .Bailey’s Circus, which opportunely came to town, and Roy and I, sitting in those reserved seats, were properly impressed. I can still remember the thrill of watching the elephants, the first of course that we had ever seen, swing past in the parade. But Uncle John gave us the personal touch. On his afternoon off, he took Roy and me to Sutro’s Park, out by the Cliff House. We rode the merry-go-round, and on real ponies, drank pink lemonade and ate popcorn, and greatest thrill of all, we went on “shoot the Chutes” several times. A flat bottomed boat was dragged up a steep incline, as I remember it about forty-five degrees, and about thirty feet long. A stream of water covered the slope, and after the boat was filled with passengers, it was released to go shooting down the chute into a pool of water, hitting with a tremendous bang, and bouncing up and down three or four times with most satisfying splashes until it finally came to a halt.

After this most exciting afternoon, we were to go to his house for dinner, and on the way home, we stopped in front of a fruit stand. Uncle John said, “Which would you rather have, grapes or a watermelon?” Roy looked at me and I looked at Roy each of us practically drooling, trying to make up our minds, when Uncle John solved the problem for us by saying, ‘We’ll take both.”

Like my mother, Uncle John had a brilliant mind. Graduating from the College of the Pacific, then located only a block from his home, when only twenty, he went to work for the San Francisco Chronicle, then the newspaper of San Francisco, and soon was one of the star reporters. Looking for new worlds to conquer, he moved on to New York, then the center of power for the country, just as Washington is today, as a special correspondent of the Chronicle, the Portland Oregonian, the Louisville Courier Journal and half a dozen other newspapers. The special correspondent was in a way the precursor of the columnist. Not only did he put on the wire stories of special interest to the papers which he served; he also wrote background stories. As a special correspondent, Uncle John was a howling success, hobnobbing with the great, president of the California Society of New York, making $12,000. a year when that was practically an unheard of income outside the business world. Nothing ever fazed him. Called upon to deliver a talk on the wonders of Yosemite, he held his hearers spellbound, even though he had never seen the place.

Unfortunately, his fatal attraction for women proved his undoing. He had only one motto for any good looking female: “She can put her shoes under my bed, any time she wants to.” Even the comely negro maid in the Atlanta hotel, where he stayed overnight, coming in to clean up the room before Uncle John was out of bed, took one look at that noble countenance and asked, “Want a little sunshine, Boss?”

Finally, his talented and charming wife divorced him, he lost his job, and was reduced to editing small country newspapers. He finally married a Southern widow, and while the Van Eatons looked down their aristocratic Roman noses at her (except my mother, who never looked down at anyone), Clyde kept him on the straight and narrow path, and when he was old and helpless, cared for him tenderly and lovingly until he died.

I could go on and write about my Aunt Belle, who was as different from the other two as night from day. They were both highly intelligent people, who used their minds. She was strictly a bundle of prejudices and sentiment, sure she knew what was best for everyone, and yet generous, and warm hearted. Except for her, I would doubt the expression “a green thumb”, yet every plant and shrub and flower grew for her in unbelievable profusion.

But enough of the Van Eatons and on to the Bainbridges. This family settled in Northern New Jersey prior to the Revolution, were unanimously Tories, emigrated to Canada for the duration, and returned after peace was declared. The family is chiefly memorable for Commodore William Bainbridge, who commanded the frigate Constitution during the War of 1812 and was one of America’s most brilliant and daring naval strategists. I only mention him because he gave my father’s oldest sister, Aunt Bebe, one of the proudest moments of her life. When “Old Ironsides” made her historic trip to the West Coast in the early part of the present century, the officers were naturally banqueted and feted in every port at which the famous frigate moored, and Los Angeles naturally put on the biggest show of all with Aunt Bebe, by virtue of her cousinship with Commodore Bainbridge, sharing the glory with the frigate’s commander, and seated between him and the mayor of Los Angeles at the banquet.

That’s about the end of the story for that family. I don’t quite understand it, but when Harriet Bainbridge married Henry Clay Bailey, she apparently forsook all her family and became a Bailey in fact as well as in name. As I remember her, she was rather a stern old character of whom the family, except my father who was her pet, stood rather in awe.

She certainly led a rugged life; out to California in 1852 as a bride of twenty; a farmer’s wife for fourteen years in Colusa County, part of the time the only white woman in the county; bearing six children in those fourteen years; back to Illinois in 1866; down to Texas in 1867; back to California in 1868, six months across the deserts of West Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and lower California, and the baby that was born during that journey c’id not live; wife of a tavern keeper on the Mexican border for eight years, and finally at long last, with eight children living, settling down in Long Beach. She milked the cow, did the yard work, and then took her ease on the front porch, scandalizing her spinster daughters in the process. Well hidden by the wisteria vine, though she cared little about that, she would rear back in her hickory rocker, put her feet on the porch railing, clamp a clay pipe in the famous Bainbridge jaw, and puff away at a great rate.

She was a lady who did as she pleased, and who made sure that the rest of the family did as she pleased also. She lived well past her golden wedding anniversary, and at a ripe old age, faced death as she had life, I am sure, without a quiver.

An article about John Dick Van Eaton’s role as Deputy Sheriff following a robbery near Placerville, CA.

Since 1851… | Mountain Democrat News and stories from |

1999 Columnists (Richard Hughey)Dec. 24, 1999 – The robbery at Bullion Bend: A posse is formed at Placerville By RICHARD HUGHEY, Democrat columnist George Ranney was a ’49er, having come around the Horn to California in September 1849. By November he was mining for gold in Hangtown, as Placerville was then called. Ranney turned to carpentry when the placer mines played out, and in that capacity he is credited, with John Studebaker, of having chopped down the infamous Hangtown Tree that served the early residents of the town so handily as a gibbet for the culprits tried in Judge Lynch’s court. The stump of the old oak still exists, buried beneath the floor of the building that Ranney helped erect at the site. Since 1861 Ranney had served as Placerville’s town constable. He was a dedicated and popular lawman with the citizens. Ranney was awakened from a deep sleep about 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning on July 1, 1864 by John Van Eaton, an El Dorado County deputy sheriff. Someone had robbed the Comstock stages on the Placerville Road, and he was needed by Sheriff William Rogers at the Courthouse to help form a posse. Other lawmen were at the Cary House in Placerville when Blair and Watson finally arrived from Sportman’s Hall in what is now Pollock Pines, where they had stopped on their way to Placerville to telegraph Rogers about the robbery. In a decision that was to cause criticism later, Rogers decided to bifurcate his posse and send two teams in different directions. Constable Ranney was teamed with deputy sheriffs Joseph Staples and John Van Eaton. Staples, a well-liked Irishman who lived in Coloma and was a member of the Neptune Company of the Placerville fire brigade, would lead the team. He was an efficient but impulsive lawman who would come to grief chasing the outlaws. Fate often exposes itself in stages, and Joseph Staples’ fate began unwinding a week earlier when he and Van Eaton, and El Dorado County Undersheriff James Hume, chased the Ike McCollum gang into a brushy area off the Mt. Aukum Road between Somerset and Fiddletown. The gangsters took defensive positions in deep cover and opened fire on the lawmen. Hume and Van Eaton returned the fire. Hume was unhurt, but Van Eaton was wounded. Staples’ horse bolted, however. Either hit by a bullet or spooked by the firing (accounts differ), the horse ran away with its enraged and cursing rider. Loose lips at the local saloon after the McCollum fray were critical of Staples’ action at the shootout, and innuendoes that he may have fled the scene in fright stung Staples to the quick. Responding to the criticism, Staples promised, “The next time I go, I’ll be brought back dead, or I’ll bring back my man.” The statement turned out to be tragically prescient. As Sheriff Rogers and the bulk of the El Dorado County posse (12 men besides the sheriff) sped east along the Placerville Road toward the scene of the robbery, Staples, Van Eaton and Ranney rode south to Diamond Springs, where they turned east and began working their way along the Pleasant Valley Road. The Pleasant Valley Road eventually joins what is now the Sly Park Road that leads directly to Pollock Pines and the Placerville Road. When the men came to the Mt. Aukum Road, which intersects with the Pleasant Valley Road, they found the tracks of six horses leading south down the road in the direction of Somerset. Staples rightly assumed that the tracks were those of the Bullion Bend robbers. They apparently had ridden south down Sly Park Road to Pleasant Valley Road, then they rode west to Mt. Aukum Road, where they turned south and made for Somerset. Fate intervened again to Staples’ detriment. Van Eaton was still suffering from the effects of the wound he had received in the shootout with the Ike McCollum gang. Staples decided wisely to send Van Eaton to summon Sheriff Rogers and the rest of the posse while he and Ranney followed the tracks of the robbery gang to see where they led. Van Eaton found Rogers and the posse at Sportsman’s Hall. The hall was a large roadhouse and inn with stables and corrals for passing stages and wagons. It had been the last major station on the Pony Express route before Placerville, and it was then a busy restaurant and hotel for the heavy eastbound traffic on the Placerville Road bound for the Comstock mines in Nevada. Sportsman’s Hall today is the third building erected at the site, the others having burned to the ground in fires. The only business at the hall now is the bar and restaurant. It’s about 12 miles east of Placerville, but for some unknown reason local residents over the years have referred to the hall as “Eleven Mile House” and “Thirteen Mile House.” The disparity may have had something to do with the straightening of the Placerville Road from time to time. At Sportsman’s Hall, Rogers had, he thought, just arrested two of the highwaymen, Thomas Finney and William Belcher. Accounts of the arrest differ, some local historians claiming Ned Blair identified the two men as part of the robbery gang and other writers insisting Charley Watson made the identification. The two men were innocent, however, neither man had been a member of the Bullion Bend robbery gang. It is questionable that either Blair or Watson would have attempted to identify them as such inasmuch as the robbery occurred at night in an area illuminated only by the coaches’ lanterns and the bandits may have worn masks. If not masks, they all had long, dark whiskers except for Glasby. Nevertheless, at Pool’s trial Watson testified he recognized Pool and Glasby as among the robbers. It is more than likely Sheriff Rogers was acting solely on a hunch, based on what he heard from the innkeeper: that two suspicious looking men showed up about midnight with their hats pulled low over their faces asking for a place to sleep. Finney and Belcher may have been guilty of something, but it wasn’t robbing the Washoe stages. Apparently Rogers discounted the obvious: that it would be extremely unlikely that two stage robbers would ask for room at a lodge barely four miles from the scene of their crime and less than an hour after it occurred. Nevertheless, Rogers was sure he had his men, so he took Finney and Belcher into custody and grilled them about the robbery neither man knew anything about. Sheriff Rogers was without question a brave and loyal lawman, but his lights were less than bright. He once led a two-month campaign against White Rock Jack and his band of renegade Digger Indians. He appointed himself commander-in-chief of the local militia unit and led the brigade to “Cockeyed” Johnson’s ranch, located about six miles above Placerville. There they waited, furnished with food and whiskey from the trading post on Johnson’s ranch. When complaints about their apparent inactivity reached them, Rogers sent back to Placerville a completely bogus report of a bloody encounter with the mountain savages, who it seemed had simply moved up to high ground in the mountains and waited for Rogers and his men to return to town. Eventually Rogers’ raiders did return to town, having stayed at Johnson’s ranch the entire time and never having fired a shot in anger, or even seen an Indian to shoot at. Thus ended El Dorado County’s Great Indian War, whereupon Sheriff Rogers’ submitted to the state Legislature his bill for $25,000 to cover the warriors’ expenses. Van Eaton was dismayed by Rogers’ action at Sportsman’s Hall. Nothing he could say would keep Rogers from lingering at the hotel, not even the fact that he and Staples discovered the tracks of six horses heading south for Somerset on the Mt. Aukum Road. Finally, Rogers finished his “lingering,” released Finney and Belcher, rounded up the posse, and headed for Somerset House. |

After Thomas Pool’s appeal was denied by the state Supreme Court, a concerted effort was made by residents in El Dorado, Monterey and Santa Cruz counties to save his life. Petitions for clemency poured in to the governor in Sacramento begging him to commute Pool’s death sentence to life in prison. Besides blatant appeals for mercy, the petitioners argued strenuously that the evidence at the trial failed to prove Pool fired a fatal shot at El Dorado County sheriff’s deputy Joseph Staples and that Pool’s children, on his ranch in the Pajaro Valley, would be left parentless, Pool being a widower.

The outpouring of support for Pool from residents in El Dorado County was quite remarkable considering the fact that Pool was judged by a local jury as one of the killers of a popular lawman. It is difficult if not impossible to understand such support, however, without taking into consideration that Placerville was home to a large number of Democrats during the Civil War. The town paper was the Placerville Mountain Democrat, and it had been denied postal privileges by the federal government for its secessionist leanings. Without doubt many of the paper’s readers were Copperheads, secessionists, fellow travelers, and fifth columnists, all sympathetic to the Southern Cause.

One local historian has pointed out that while the majority of residents in the Pleasant Valley area were loyal to the Union, there were also a number of Confederate sympathizers in the valley and animosities between the two groups had been hot. Rumors persist that 12 Copperhead residents had been murdered and buried in the Ringgold Cemetery on Quarry Road, and that secessionists had cached hordes of weapons and ammunition in Dead Head Gulch, a steep ravine near Newtown.

Furthermore, while Preston Hodges’ rather pathetic characterization of the Bullion Bend robbery, and by extension the shootout at Somerset House, as a “military expedition” seems disingenuous to modern minds, it made a substantial impact on the minds of many of Hodges’ contemporaries in San Jose and Placerville. Surely, many believed that poor Tom Pool was in fact a “prisoner of war” and should be treated as such.

A stunning document begging for Pool’s life was a petition signed by George Parsons, A. Burnil, C.L. Crisman, H.C. Murgotten, John McCall, Charles Hart and Amos Van Vleck. If those names sound familiar, they should. These seven men were among the 12 jurors who took 15 minutes at Pool’s trial to find him guilty of the first-degree murder of deputy Staples.

An equally stunning petition for mercy was filed by William Rogers, Sheriff of El Dorado County; William Carpenter, Clerk of the County of El Dorado; A.L. Lowry, Deputy County Clerk; J.J. Williams, District Attorney for the County of El Dorado, who prosecuted Pool; James B. Hume, Undersheriff of the County of El Dorado, and D. DeGolia, Pool’s jailer.

Nor had Pool been forgotten by his old friends in Monterey County who remembered his “courageous” defiance of Gov. Waller to hang at the appointed hour the murderer Jose Anastasio. Nineteen citizens, including the Monterey County Clerk, filed a petition seeking clemency for their ex-undersheriff alleging him to be a “peaceable and law abiding citizen” and the unfortunate father of several “motherless children.” Recalling the lack of evidence showing Pool to be one of Staples’ shooters, the petitioners expressed the opinion that, under the circumstances, life in prison was better fit for the crime. Among the signers of the petition was the Honorable William H. Ramsey, District Court Judge of the County of Monterey.

Several individual residents of Monterey County filed petitions in Pool’s behalf, and a joint petition was filed on behalf of 47 residents of Monterey and Santa Cruz counties.

Perhaps the most interesting document sent to the governor was a Statement of Facts dated Sept. 26, 1865, three days before Pool’s execution. It had been drafted by James Johnson, Pool’s attorney, and signed by El Dorado County deputy sheriff John Van Eaton. It asked neither for commutation nor confirmation of Pool’s death sentence, however; it simply recited a number of facts concerning his capture and imprisonment in Placerville by the deputy who guarded and interrogated him. In that sense it was perhaps the most persuasive of the documents filed on Pool’s behalf.

Van Eaton stated that when Pool was captured there was no clue as to Pool’s associates, nor where they had come from or where they were going when they left Somerset House. Four days later Van Eaton interviewed Pool at the jailhouse and secured Pool’s cooperation. Pool gave Van Eaton the names and detailed descriptions of his fellow stage robbers, which information appeared in newspapers the next day throughout Northern California, including Placerville and San Jose. Pool told Van Eaton that the gang had come from Santa Clara County and planned to return to San Jose or travel on to a hideout on the Kings River near Visalia. He thought the men would go back to San Jose, however. Pool gave Van Eaton the names of the Confederate sympathizers in Visalia who were expected to assist the robbers if they showed up there, and he also gave him the names of the members of the larger group of conspirators in San Jose who supported but did not accompany the gang to El Dorado County. Through Pool’s assistance, Van Eaton continued, the authorities were successful in recovering all of the bullion and most of the gold dust.

Finally, Van Eaton stated that all of the information Pool provided proved to be accurate and truthful, and without out it the Bullion Bend gang no doubt would have continued with more robberies and “unlawful combination.” Because of Pool’s cooperation, the entire Confederate organization was broken up.

Accompanying Van Eaton’s Statement of Facts was a petition for clemency of the same date signed by attorney James Johnson. It is a somewhat rambling document voicing the same old arguments and generalities. Johnson also filed a addendum to the petition that bordered on incoherence three days after Pool had been hanged, to what purpose is unknown, although it may be noted that Johnson begins the original petition by saying he intended to file a petition on behalf of Pool but didn’t have the time to do so.

Lawyer Johnson, who had been a county judge in Placerville for 11 years, begins his petition with a simple plea for sympathy and mercy, which, he insists, have some place in the “premises.” Perhaps in desperation, Johnson reaches for a farfetched analogy. Pool, he points out, was part of the “rebellion.” Therefore, he asks rhetorically, should Pool be executed for his crime while Confederate General Robert E. Lee goes free? Pool never fired the fatal shot, Johnson insists. It was Bulware who killed Staples. Without Pool’s cooperation the Bullion Bend gang would never have been brought to justice. Pool was not given a fair trial in Placerville, and the California Supreme Court erred when it denied him a new one.

Johnson also complains that the prosecution was ramrodded by the attorney for Wells Fargo, that great excitement occurred at the trial, and that it was interrupted by “many inflammatory speeches.” Pool’s last words to him before his hanging were, “I am no murderer. I feel as if now, for the first time, I am about to be tried before a court of justice.”

Perhaps surprisingly under the circumstances the governor refused to act. Nothing in the governor’s pardon file in Pool’s case discloses his thinking. Nevertheless, one cannot help but think that the spectre of Jose Anastasio must have been standing at his side as he read the petitions residents had filed on behalf of former Undersheriff Thomas Pool of Monterey County.

On page two of the Saturday, Sept. 30, 1865 edition of the Placerville Mountain Democrat, appeared the following story: “Executed: Precisely at 12 o’clock yesterday, Thomas B. Poole, implicated in the stage robbery and the killing of Deputy Sheriff Staples, in this county, in July, 1864, suffered the extreme penalty of the law. He calmly ascended the scaffold, pleasantly conversed with the officers having him in charge, and the Rev. Mr. Wallace, cordially shook each by the hand, and fearlessly resigned his spirit to its God. He smiled on all, and seemed perfectly resigned. He made no public address. While the cap was drawn over his face and his arms and legs were being pinioned, he stood perfectly composed. He died almost without a struggle and in a few seconds.”

___________________________________________________________________________

From the “Mountain Democrat, April 7, 2000, by Columnist Richard Hughey:

Perhaps the most interesting document sent to the governor was a Statement of Facts dated Sept. 26, 1865, three days before Pool’s execution. It had been drafted by James Johnson, Pool’s attorney, and signed by El Dorado County deputy sheriff John Van Eaton. It asked neither for commutation nor confirmation of Pool’s death sentence, however; it simply recited a number of facts concerning his capture and imprisonment in Placerville by the deputy who guarded and interrogated him. In that sense it was perhaps the most persuasive of the documents filed on Pool’s behalf.

Van Eaton stated that when Pool was captured there was no clue as to Pool’s associates, nor where they had come from or where they were going when they left Somerset House. Four days later Van Eaton interviewed Pool at the jailhouse and secured Pool’s cooperation. Pool gave Van Eaton the names and detailed descriptions of his fellow stage robbers, which information appeared in newspapers the next day throughout Northern California, including Placerville and San Jose. Pool told Van Eaton that the gang had come from Santa Clara County and planned to return to San Jose or travel on to a hideout on the Kings River near Visalia. He thought the men would go back to San Jose, however. Pool gave Van Eaton the names of the Confederate sympathizers in Visalia who were expected to assist the robbers if they showed up there, and he also gave him the names of the members of the larger group of conspirators in San Jose who supported but did not accompany the gang to El Dorado County. Through Pool’s assistance, Van Eaton continued, the authorities were successful in recovering all of the bullion and most of the gold dust.

Finally, Van Eaton stated that all of the information Pool provided proved to be accurate and truthful, and without out it the Bullion Bend gang no doubt would have continued with more robberies and “unlawful combination.” Because of Pool’s cooperation, the entire Confederate organization was broken up.

Accompanying Van Eaton’s Statement of Facts was a petition for clemency of the same date signed by attorney James Johnson. It is a somewhat rambling document voicing the same old arguments and generalities. Johnson also filed a addendum to the petition that bordered on incoherence three days after Pool had been hanged, to what purpose is unknown, although it may be noted that Johnson begins the original petition by saying he intended to file a petition on behalf of Pool but didn’t have the time to do so.

Lawyer Johnson, who had been a county judge in Placerville for 11 years, begins his petition with a simple plea for sympathy and mercy, which, he insists, have some place in the “premises.” Perhaps in desperation, Johnson reaches for a farfetched analogy. Pool, he points out, was part of the “rebellion.” Therefore, he asks rhetorically, should Pool be executed for his crime while Confederate General Robert E. Lee goes free? Pool never fired the fatal shot, Johnson insists. It was Bulware who killed Staples. Without Pool’s cooperation the Bullion Bend gang would never have been brought to justice. Pool was not given a fair trial in Placerville, and the California Supreme Court erred when it denied him a new one.

Johnson also complains that the prosecution was ramrodded by the attorney for Wells Fargo, that great excitement occurred at the trial, and that it was interrupted by “many inflammatory speeches.” Pool’s last words to him before his hanging were, “I am no murderer. I feel as if now, for the first time, I am about to be tried before a court of justice.”

Perhaps surprisingly under the circumstances the governor refused to act. Nothing in the governor’s pardon file in Pool’s case discloses his thinking. Nevertheless, one cannot help but think that the spectre of Jose Anastasio must have been standing at his side as he read the petitions residents had filed on behalf of former Undersheriff Thomas Pool of Monterey County.

On page two of the Saturday, Sept. 30, 1865 edition of the Placerville Mountain Democrat, appeared the following story: “Executed: Precisely at 12 o’clock yesterday, Thomas B. Poole, implicated in the stage robbery and the killing of Deputy Sheriff Staples, in this county, in July, 1864, suffered the extreme penalty of the law. He calmly ascended the scaffold, pleasantly conversed with the officers having him in charge, and the Rev. Mr. Wallace, cordially shook each by the hand, and fearlessly resigned his spirit to its God. He smiled on all, and seemed perfectly resigned. He made no public address. While the cap was drawn over his face and his arms and legs were being pinioned, he stood perfectly composed. He died almost without a struggle and in a few seconds.”