9/23/1739 – 11/21/1833

From Kirke Wilson on August 31st, 2005, in response to a question from Mike Moffitt as to the location of the Thomas Simpson grave:

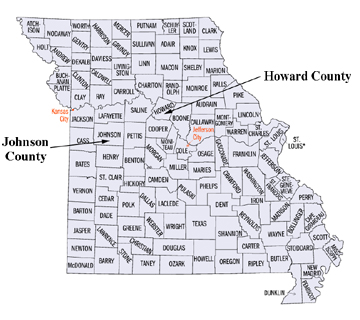

Thomas Simpson died September 21, 1833 at the home of his son William in Johnson County, Missouri. He was 95 years old. He was buried at his son’s farm twelve miles east of Warrensburg. His wife Mary Knight Simpson died in September 1836 at the age of 85. She was buried near her husband. In 1951, the Simpson graves were located on the J. W. Crowder farm in Post Oak Township and were marked with tombstones at some point. The graves are among those of several Kimsey and Simpson relatives. The William Simpson family left Johnson County in 1838 and 1839 and moved to Platte County in the newly-opened Platte Purchase. To my knowledge, no one has found the Thomas Simpson grave in recent years although several have gone searching. Kirke Wilson

____________________________________________________

From the notes of Kirke Wilson, May, 1991.

Thomas Simpson (1739-1833)

m. first wife unknown, 4 sons and 3 daughters cl760-cl780

m. Mary Knight (cl751-1836), 2 sons/2 daughters 1783-1793

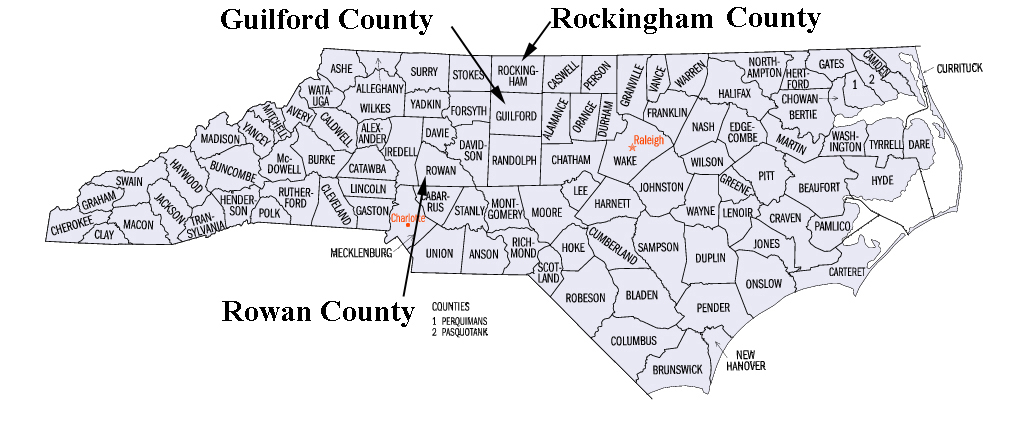

second son/fourth child, William b. 1793, Rockingham Co, NC

family to Warren Co, Tennessee c. 1804, Howard Co, Missouri

c^ 1820 and Johnson Co, Missouri in 1830s Thomas and Mary

Simpson both died and are buried in Johnson Co, Missouri

It is possible that Thomas Simpson was a signer of the Watauga Petition, in which members of several frontier communities of Tennessee declared their intensions “to adhere strictly to the rules and orders of the Continental Congress and in open committee acknowledge themselves indebted to the United Colonies their full proportion of the Continental expense.” However, whether this Thomas Simpson was on ancestor is unclear. The following from pages 45 to 47 of “FOR WE CANNOT TARRY HERE” by Kirke Wilson, San Franciso, 1990:

Revolution on the Frontier

The self-sufficient pioneers on the frontier were not inconvenienced by British taxes on luxuries not available on the frontier nor by taxes on documents and publications. While they were aware of the underlying issues of political theory, the frontier settlers were primarily concerned about their land. They were aware of their land claims and concerned about British efforts to maintain alliances with the Indians. On the frontier of Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee, the Revolution was : a war to hold land against the Indians and their British advisors while strengthening land claims west of the mountains.

While the representatives to the Second Continental Congress were debating the Declaration of Independence at Philadelphia during the early summer of 1776, groups of settlers were gathering on the frontier to pledge their support for the rebellion. In June 1776, representatives of the three Kentucky stations convened at Harrodsburg. Styling themselves the Committee of West Fincastle of the Colony of Virginia, the Kentuckians declared:

…we sincerely concur in the measures established by the Continental Congress and Colony of Virginia. And willing to the utmost of our abilities to support the present laudable cause by raising our Quota of men and bear a proportional share of Expense that will necessarily accrue in the support of our common

Liberty.8

In addition to the commitment to political liberty, the Kentuckians asserted their commitment to the economic liberty of the land they had claimed,

…as the Proclamation of his Majesty for not settling on the Western parts of this Colony, is not founded upon Law, it cannot have any Force…9

At the same time, the Tennessee settlers were collecting at Watauga,

…we were alarmed by the reports of the present unhappy differences between Great Britain and America on which report (taking the now united colonies for our guide) we proceeded to

choose a committee….This committee (willing to become a party in the present unhappy contest) resolved.-.to adhere strictly to the rules and orders of the Continental Congress and in open committee acknowledged themselves indebted to the United Colonies their full proportion of the Continental expense.10

As part of their contribution to the revolutionary cause, the Watauga pioneers organized a rifle company under Capt. James Robertson. The rifle company was offered to assist the colonies but was assigned by the Wataugans to the defense of their own frontier.

The settlers, calling themselves the Washington District, formed a court and adopted the laws of Virginia but petitioned the Provincial Council of North Carolina,

…that you may annex us to your Province (whether as county, district or other division) in such manner as may enable us to share in the glorious cuase of Liberty, enforce our laws under authority-nothing will be lacking or anything neglected that may add weight (in the civil or military establishments) to the glorious cause in which we are now struggling or contribute to the welfare of our own or ages yet to come.”

On July 5,1776, 111 settlers signed the Watauga Petition to North Carolina. These pioneers on the Nollichucky and Watauga Rivers included John Carter, William Been (Bean), John Sevier, Charles and James Robertson and others including Thomas Simpson (ca. 1731-1835).12

North Carolina, busy with its own problems, was slow to respond to the frontier petitioners. In December 1776, the North Carolina Provincial Congress, including delegates from the Watauga settlements, adopted a Constitution which established the Washington District as part of North Carolina. An ordinance adopted at the same time named 21 Wataugans, including Thomas Simpson, to serve as members of the Washington District Court. It is unclear whether this court ever functioned because a second ordinance was passed in early 1777 establishing Washington County and naming 14 members of the county court. Thomas Simpson was not a member of the second court. The original area of Washington County, North Carolina has subsequently become the 95 counties of Tennessee.13

The Thomas Simpson who signed the Watauga petition and who was a member of the first Washington District Court had come to the settlement from Virginia. Thomas Simpson may have arrived at Watauga late in 1775 or early in 1776 since he was not among the settlers allocated land purchased from the Indians in March 1775.”

Copied from pages 121 to125 of “FOR WE CANNOT TARRY HERE” by Kirke Wilson , San Francisco, 1990.

The Simpson Family in Tennessee

The first member of the Simpson family in America achieved appropriately mythic proportions in family legend by living to the age of 104 and recovering from blindness. He may even have grown a third set of teeth. His long life carried him from Scotland to colonial America before settling on the frontier in Tennessee and later Missouri. Like many myths and legends, the story of Thomas Simpson is difficult to document with any certainty.

Born in Scotland about 1731, Thomas Simpson came to America as a young man leaving, according to his grandson, “a valuable estate in Scotland which his heirs never received.”77 According to one, unconfirmed source, he was unsuccessful in claiming a family estate in Scotland valued at several million dollars because family papers which would have proven his claim were destroyed by fire.76

Equally apocryphal, another source suggests that Thomas Simpson was the younger son of a Scottish baron who left Scotland and traveled through England and France on his way to Virginia.79 He arrived in North America sometime before the Revolutionary War and lived in Virginia where he may have served as a “colonial soldier of Virginia.”80 He would have been in his mid-twenties during the French and Indian War and lived in Virginia where the colonial militia was activated repeatedly. Thomas Simpson is not listed in the rosters of the Virginia colonial militia.” He appears to have arrived on the Tennesse frontier at Watauga sometime in late 1775 or early 1776.82

According to one grandson, Thomas Simpson served seven years in the Revolutionary War without injury.83 One family legend, completely without confirmation, places Thomas Simpson at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-1778, where his son was killed.” According to another grandson, Thomas Simpson “knew General Washington well.”85 Despite these claims by adult grandchildren who might have heard the stories from an elderly grandfather more than sixty years earlier, there is no confirmation of Thomas Simpson’s service in the war. He is not listed among any of the Watauga militia units whose records have survived like those who fought at Kings Mountain in 1780. Since he would have been nearly fifty years old at the time, it is likely that his service would have been to defend the settlements while younger and more experienced frontiersmen were fighting in South Carolina. Few records were kept during that period and many records were lost. Although he lived fifty years after the end of the war, there is no record that Thomas Simpson applied for a pension for service in the Revolutionary War.” He is, however, listed as one of the soldiers of the Revolutionary War buried in Missouri.87

It is possible, but not likely, that Thomas Simpson, as his grandson claimed, was acquainted with General Washington. Since Washington never reached the frontier during the Revolutionary War, any acquaintance would have been the result of earlier experiences, perhaps during the French and Indian War when Washington was Commander-in-Chief of the Virginia Regiment and militia. Washington was a well-known figure in Virginia as a result of long public service in military and civil office. He traveled frequently to administer his plantations, to attend General Assembly sessions at the colonial capital at Williamsburg and to lead military campaigns. During the twenty years before the Revolutionary War, Washington traveled extensively along the Virginia frontier.”

During the period after the Revolutionary War, Thomas Simpson and his family moved several times. They apparently lived only briefly in the Watauga area before relocating.*9 According to a grandson, the family settled for a time near Charleston, South Carolina before returning to Tennessee and later moving to Missouri.90 The Thomas Simpson family lived for a time on an old cotton plantation in Rockingham County, North Carolina in the 1790’s before moving over the mountains to a farm in Warren Country. Tennessee sometime between 1803 and 1808 when Thomas Simpson would have been over seventy years old.91 The Simpson family may have lived briefly in East Tennessee before settling in Middle Tennessee. A Thomas Simpson was a taxpayer in Blount County in 1801 92 and a Thomas Simpson was a taxpayer in Anderson County in 1802.93 In each case, Thomas Simpson owned no land nor slaves and lived in a household with a single adult male. In September 1806, Thomas Simpson was, along with John White and twenty-one others, one of the original settlers of White County.94 The following year, White County was divided with the area southwest of the Caney Fork becoming Warren County. Thomas Simpson was not among the 313 residents southwest of the river who petitioned for the division of White County in 1806 nor among the incomplete list of early settlers of Warren County.95 Sometime soon after the formation of the new county, Thomas Simpson and his family settled in Warren County where they lived into the 1820s.96 Tennessee land, tax and census records for the period before 1820 are incomplete. The fragmentary records which survive do not show that Thomas Simpson nor his family owned property in Warren County.97

Warren County was established in 1807 on the highland rim of the Cumberland Mountains in central Tennessee. The area was opened to settlement after the Third Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse in 1805 extinguished Cherokee title to a large area in Central Tennessee and southern Kentucky north of the Cumberland River including most of the Cumberland Plateau. The 1805 Treaty superseded the 1798 Treaty of Tellico in which the United States obtained two parcels of Cherokee land in exchange for an agreement that the Cherokee would possess “the remainder of their country forever.” In 1831, the United States ordered the removal of all Cherokee from Tenessee, the infamous “Trail of Tears.”98 The country was settled during the first decade of the nineteenth century. By 1808, a county government was organized and the following year a county seat had been selected at McMinnville. By 1810, a union church called Shiloh, an Academy and a log school had also been established in Warren County.” Warren County was settled rapidly. The population reached 5725 by the time of the census in 1810 and 10,348 by 1820. The population continued to grow into the 1830s when out-migration reduced the population by one-third.100

According to the family records, Thomas Simpson married twice and had a total of eleven or twelve children.101 Nothing is known about his first wife other than she had three or four children.102 His second wife, whose maiden name was Knight (1752-1837), bore him an additional eight children including six daughters and two sons, James and William.103 William Simpson, the frontier preacher, was born in Rockingham County, North Carolina in 1793 and moved with his family to Tennessee in 1808 where he married Mary Kimsey (1797-1858) in 1813 and established his own Warren County farm.104 Over the following twenty-three years, William and Mary Kimsey Simpson would have eleven children including six daughters and five sons, all born and raised on the frontier of Tennessee and Missouri.105 The youngest of eight children of James and Mary Croly Kimsey, Mary Kimsey Simpson was born in Virginia.106 Her mother and father, James and Mary Kimsey, had immigrated from Ireland and settled in Virginia about the time of the Revolutionary War.

The Kimsey family originated in Scotland where Benjamin McKimsey, an older brother of James born in 1725, fought at the Battle of Culloden and fled to safety, with his family to Ireland. According to family legend, McKimsey and his party crossed Ireland on foot before catching a ship to Maryland where both Benjamin and his brother James, with their name simplified to Kimsey, settled. Before 1750, the two brothers relocated to Virginia where Benjamin settled in Augusta County and James in Henry County. About 1768, James moved to Augusta County near his brother where both lived during the Revolutionary War. The brothers, after some delay, swore loyalty to Virginia in 1778. About 1785, the brothers moved again. James Kimsey and his family settled on the Duck River in what is now Tennessee where two Kimsey daughters married Simpson sons.107 Called “Polly” by the members of her family, Mary Kimsey married William Simpson and her older sister Elizabeth Kimsey married William’s older brother James Simpson.108 James Kimsey was killed in the War of 1812, presumably in Tennessee. Mary Kimsey, the daughter of James Croly, moved, with her daughter and her Simpson in-laws, to Missouri where she died in 1835.109

After several years of economic expansion and prosperity, the United States economy collapsed in 1819. Credit vanished, commodity prices fell, land values evaporated and banks failed. In Kentucky and Tennessee, where the economy depended on credit and land speculation, the Panic of 1819 was particularly severe and persistent. Farmers who had borrowed money to buy land during the boom years found themselves with crops they could not sell and loans they could not repay. Although opinion was divided, both Kentucky and Tennessee enacted debtor’s relief measures in 1819 to delay or prevent forced sales of property or equipment to repay loans.110 For many families, the relief was too little or too late. They had lost their farms in foreclosure or were burdened with hopeless debt. For many such families, the economic collapse stimulated migration toward places where cheap land might be available and where a pioneer could start anew.

Sometime between 1820 and 1823, three generations of the Simpson family moved from Warren County in central Tennessee to Howard County in central Missouri.111 The family included the elderly Thomas Simpson, now ninety years old, and his wife, as well as their son William with his wife Mary and their children Ellen, Thomas, and Benjamin. The extended family also included the widow, Mary Croly Kimsey, as well as James and Elizabeth Simpson and their children. Like many other families, the Simpsons were bound for the Boonslick region of Central Missouri.

The following was copied from portions of pages 33 through 45 from “A VERY IMPROVING STATE: THE SIMPSON FAMILY IN NORTH CAROLINA, 1755 – 1804” by Kirke Wilson, 1995.

The Thomas Simpson Family in Guilford County, North Carolina

Thomas Simpson (1739-1833), the oldest child of Richard and Elizabeth Simpson was a teenager when his family moved from Maryland to North Carolina. He appears tc have lived with his father on Mears Fork for several years before moving to his own fare on adjacent property. He first appeared on the Rowan County tax list in 1768.89 At about the same time, Thomas Simpson married a woman whose name is unknown. Together they had four sons and three daughters between about 1765 and 1780.90

In the 1770s, Thomas Simpson may have been at a point of transition in his life. His first wife, the mother of his seven children, had died. He had lived and farmed near his father all his adult life but he may have considered moving out on his own. He may have left his family at Mears Fork, where his children would have been old enough to support themselves by working on their grandfather’s farm, and explored opportunities on the new frontier opening on the North Carolina-Tennessee-Virginia border 150 miles to the West. While this is possible, it is somewhat out of character for Thomas Simpson. He made several moves during his long life but, in every other case, he appears to have moved with his family. He does not appear to have had other military service and it is uncertain whether he could sign his name. While he may have had an opportunity to explore frontier opportunities in 1776, it is most likely that the Thomas Simpson of Mears Fork was not the same man who signed the Watauga petition and served briefly as an elected member of the Washington District Court in what later became Tennessee. While Thomas Simpson of Haw River could have been at Watauga in July 1776, it would have been inconsistent with his life before or after the Revolution.

Whether or not Thomas Simpson, then in his late 30s, visited Watauga in 1776, he participated in the Cherokee campaign of 1776 and returned to Guilford County. His grandson reported, more than a century later, that Thomas Simpson “served seven years and never received a scratch” in the Revolutionary War.91 Contrary to that legend, there is no evidence of subsequent service by Thomas Simpson in the Revolutionary War that swirled around his Guilford County home.92 In February 1779, he purchased 50 acres from William Williams for 50 pounds. The land Thomas Simpson bought was on the east side of his father’s Mears Fork property. Triangular in shape, the land was bounded on the west by Line Branch and on the east by property William Williams had owned since 1758.93 According to a contemporary description, the land was,

…on Mairs Fork waters of Haw R., begin at the mouth of Line Br. joining Richard Simpson’s line, down the creek to a Spanish oak, by a line of marked trees agreed upon between William Williams & Richard Simpson to the S line on William Williams cornering on a red oak…94

The Guilford County land Thomas Simpson purchased in 1779 was, like his father’s property, part of the 640 acres Lord Granville granted George Jurdan, Jr. on Mears Fork and the Haw River. The Thomas Simpson land was bisected by Iron Works Road. In 1780, North Carolina granted 558 acres to William Dixon. The Dixon land was on the south boundary of the Richard Simpson and Thomas Simpson land. In August 1782, Thomas Simpson purchased 50 acres from William Dixon. The 50 acres was on the north edge of Dixon’s land and extended across much of the southern boundary of the land Thomas Simpson and his father owned.95

Guilford County After the Revolution

During the period he was acquiring land in Guilford County, Thomas Simpson married Mary Knight (c. 1751-1836) and began a second family. Mary Knight was from a family that was closely associated with the Simpsons of Haw River. She was probably the daughter of David Knight of Rockingham and Grayson Counties, Virginia who lived in Orange County, North Carolina from 1755 until his death between 1775 and 1781. Her brother Thomas (c. 1740-1824) appears to have married Elizabeth Simpson, Thomas’ younger sister, in 1768 and her sister Sarah Elizabeth married Thomas’ younger brother Nathaniel in 1785.103 Thomas Knight served in the Revolutionary War from Guilford County and later settled on Jacobs Creek in Rockingham County. He sold his Rockingham County land to his son Thomas Knight, Jr. in May 1805 and moved to Wilson County, Tennessee about 1808. He died in Wilson County in 1824.104

Thomas and Mary Knight Simpson had four children between 1783 and 1793. The oldest child, James, (n.d.-1852) married Elizabeth Kimsey (1790-1865).105 Two daughters followed. Jane married Lazarus Matthews and Farraba married William Bragg (or Blagg). The youngest child, William (1793-1858), was born in Rockingham County June 27, 1793 and married Mary Kimsey (1797-1858), a younger sister of Elizabeth, in 1813 in Tennessee. William Simpson would later become a frontier preacher in Tennessee, Missouri and Oregon.106 Although William Simpson would preach as a Baptist, his father was active as a Methodist in North Carolina and for the rest of his life. Two grandsons, writing a century later about the grandfather they had known as children, each remembered that he had been a devout Methodist.107

Raised in Maryland where the Church of England was the established church, Thomas Simpson became a Methodist sometime after the Revolution when the Methodist Episcopal Church began sending circuit-riding preachers to the mid South. By 1791, he was selling part of his Guilford County property to build a Methodist Church. He sold one and one-half acres on the south edge of the land he had acquired from William Dickson nine years earlier. The buyer was Francis Asbury (1745-1816), a tireless frontier evangelist and Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church. The most prominent Methodist clergyman of his time, Bishop Asbury traveled 270,000 miles preaching the gospel to frontier communities in Kentucky, Tennessee and the Carolinas between 1771, when he was selected by John Wesley to preach in North America, and 1816. At a time when roads were little better than trails in the wilderness, Asbury used horses, wagons and carriages to reach the homes, taverns, barns, court houses and open fields where pioneers gathered to hear the gospel. Over 45 years, he delivered 16,425 sermons while constantly on the move.

In his Journal, Bishop Asbury recorded 72 visits to North Carolina including several to Guilford County and Rockingham County. Like Charles Woodmason, the Anglican evangelist in the Carolinas a generation earlier, Asbury was critical of the roads, housing and people he encountered. In July 1780, he passed through the area complaining about bad roads and inattentive congregations,

…over rocks, hills, creeks and pathless woods and low land…for there was no proper road¡ªthe people’s minds were in confusion; poor souls¡ªthey seem hardened and no preaching affects them, at least not mine; they are exceedingly ignorant withal.108

The following day, Asbury observed, “I can see little else but cabins in these parts built with poles.” After a sermon to a congregation of sixty, he expressed his frustration and relief, “I was glad to get away, for some were drunk, and had their guns in meeting.”109 The next day, encountering another piedmont congregation, Bishop Asbury recorded in his Journal,

…the people are poor, and cruel one to another; some families are ready to starve for want of bread, while others have corn and rye distilled into poisonous whiskey.110

During a 1786 visit to Newman’s Chapel in Rockingham County, Asbury found poverty and deprivation, “Provisions here are scarce: some of our friends-are suffering.”111 A few days later, vowing never again to return to nearby Orange County, he complained,

0, what a country this is! We can but just get food for our horses. I am grieved, indeed, for the sufferings, the sins, and the follies of the people.112

In 1787, after preaching at Newman’s Chapel, Asbury observed tersely, “…the people were rather wild.”113 Newman’s Chapel, where Asbury preached in March 1786 and

43 April 1787, was on Iron Works Road near the boundary between Rockingham and Orange County approximately ten miles from the Simpson farm on Mears Fork.

The Methodist Church began sending circuit-riding preachers into the North Carolina backcountry before the Revolutionary War. Residents of the Haw River area received regular visits after the Yadkin circuit was formed in 1780. Within three years, a separate circuit was created to serve Guilford County and what would soon become Rockingham County. Bishop Asbury first visited the Yadkin circuit in 1783 and visited the Haw River area annually from 1786 to 1788 and from 1793 to 1795 as well as visiting the area again in 1799.114

Bishop Asbury completed his twenty-first visit to North Carolina in January and February 1791.115 He returned that March traveling with Bishop Thomas Coke and preached again at Newman’s Chapel and at Arnett’s in Rockingham County where he had conducted services in 1785 and 1786. “6 By 1791, Thomas Simpson and his family are likely to have had numerous opportunities to hear the gospel from circuit-riding Methodists. During one of these visits, Thomas Simpson and Bishop Asbury appear to have concluded that there was need for a Methodist chapel in the northern part of Guilford County. In March 1791, Bishop Asbury paid Thomas Simpson five shillings for the one and one half acres described as:

…near the dwelling house of said Thomas Simpson…for the purpose of erecting thereon a church chapel meeting house for the worship of Almighty God.117

The chapel, called Simpson’s Methodist Church, was located on Iron Works Road in northern Guilford County within a mile of the Haw River and Rockingham County line.118 In his Journal, Bishop Asbury does not mention his 1791 transaction with Thomas Simpson nor ever preaching at Simpson’s Chapel.

Thomas Simpson and his family continued to live in Guilford County until 1792. At the time of the first national census in 1790, Thomas Simpson and his wife were part of a twelve-person household including two male children over the age of sixteen, two boys under sixteen and seven women. They lived in the same area as the elderly Richard Simpson, Senior, and his wife and Richard Simpson, Junior, and his household of eight.119 In 1790, Thomas Simpson also served on a Guilford County jury.120 Within two years, Thomas Simpson and his family decided to leave the Mears Fork area and move a few miles north into Rockingham County. His three oldest sons, Richard, Nathaniel and Peter Ryan, perhaps with financial assistance from their father, had each acquired land in Rockingham County. The young Simpsons all bought land in an area where Thomas Knight, a close family associate and relative by marriage, had lived since the Revolutionary War. In January and February 1792, Thomas Simpson sold his 98 1/2 acres in Guilford County to his neighbor William Williams and moved to Rockingham County.121

The Mears Fork land that Thomas Simpson sold his neighbor William Williams in 1792 was resold in 1795 to Stephen Gough and his teenage son Daniel Gough. In 1797, Daniel Gough followed the Thomas Simpson family to Jacobs Creek in Rockingham County where he bought 50 acres from Thomas Simpson’s son Richard and married Thomas Simpson’s daughter Sarah.122 When Thomas Simpson’s brother Richard died in 1803, his will left “50 ac. near where my bro Thomas did live” to his son William.123 Several descendants of Richard Simpson continued to live in Guilford County after Thomas Simpson moved across the county line into Rockingham County. Nathaniel Simpson, most-likely the son of Thomas Simpson, died in Guilford County in 1830 leaving his wife Sarah and sons named William and Thomas.124

The following was copied from portions of pages 53 and 54 from “A VERY IMPROVING STATE: THE SIMPSON FAMILY IN NORTH CAROLINA, 1755 – 1804” by Kirke Wilson, 1995.

The Thomas Simpson Family in Rockingham County

A few months after selling his Mears Fork property in Guilford County, Thomas Simpson purchased land approximately nine miles to the north on the upper reaches of Jacobs Creek in Rockingham County. Jacobs Creek flows north into Brush Creek and the Dan River draining a large area of Rockingham County north and west of State Route 65 and east of U.S. 220. The area is immediately north of the town of Bethany, North Carolina and approximately fifteen miles from the Virginia border.142 In June 1792, Thomas Simpson paid “25 pounds actual gold and silver” to Charles Bruce of Guilford County for 150 acres on Bear Branch of Jacobs Creek. The land lay high on a ridge on the north and south sides of the branch. Two streams entered the property on 54 the east and joined to form Bear Branch in a steep valley in the southwest comer. The land was bounded on the south and west by the property of Samuel Short.143

In March 1796, Thomas Simpson’s oldest son Richard purchased 121 acres on the waters of Jacobs Creek from John Conner for 36 pounds. The Richard Simpson land was bounded on the south by William Conner, on the west by Samuel Short and Andrew Conner, on the north by Charles Bruce and on the east by former governor Alexander Martin. Thomas Simpson was a witness to the 1796 transaction.144 In August 1796, Peter Ryan Simpson, another son of Thomas Simpson, acquired 106 acres on Rocky Fore of Jacobs Creek. He paid 60 pounds currency to Adam and Allafa Trollinger for an oddly-shaped parcel north and east of Alexander Martin and south and west of Nathaniel Linder.145 The following year, Richard Simpson sold a 50 acre parcel to his brother-in-law Daniel Gough for 15 pounds. The land was the southern part of land Richard Simpson had purchased eighteen months earlier.146

Rockingham County, the area immediately north of Guilford County to the southern boundary of Virginia, had been formed in 1785,

…by an east and west line, beginning at Haw River bridge, near James Martins…that other part of the said county of Guilford, which lies north of the said dividing line shall henceforth be erected into a new and distinct county by the name of Rockingham.147 The area was part of the Granville District and was first settled in the 1750s. The settlers established small farms along the Dan River and its tributaries and produced tobacco, grains and livestock.

The following was copied from portions of pages 61 through 66 from “A VERY IMPROVING STATE: THE SIMPSON FAMILY IN NORTH CAROLINA, 1755 – 1804” by Kirke Wilson, 1995.

It is unclear whether or not Thomas Simpson could read and write. He had grown up in Maryland in a farming family of modest means and had lived all his adult life in rural areas of North Carolina where education was limited and literacy was not essential. Rather than signing his name, Thomas Simpson made his mark in 1785 when acting as a witness at his brother Nathaniel’s marriage and in 1796 when his son Richard purchased land. He also made his mark in 1804 when selling land in Rockingham County.162 In other land transactions, he may have signed his name.163 It is possible that he was illiterate but it is also possible that there is another explanation for his inability to sign his name. According to a letter written by his grandson in 1897, Thomas Simpson …was blind for many years-within a few years of his death, his eyesight came to him again. He could see to read common print without glasses.164 While the grandson may not have observed the recovery or have had direct knowledge of his grandfather’s reading ability, the dramatic story suggests that Thomas Simpson may have been blind rather than illiterate during the years in Rockingham County.

When Thomas Simpson moved to Rockingham County in the 1790s, the county population was 6219 including 1105 slaves. By 1810, the population had increased by 66 percent to 10,316 and the number of slaves had increased by 91 percent to 2114.168 As transportation improved, larger land owners shifted from self-sufficiency farming to export commodities like tobacco and cotton. The shift to an export economy also resulted in increasing concentration of wealth and increased used of slave labor. Like the pattern that drove the Simpson family out of Maryland a half century earlier, the increasing concentration of wealth pushed out many of the middling farmers who could not accumulate the wealth to acquire new land and slaves. The new land was necessary to prevent declining crop yields as land became exhausted as a result of repeated planting of tobacco or cotton. Slave labor enabled planters to increase production of commercial crops like tobacco and cotton.169

The Simpson family, over more than a century in areas where slaves were common, had never owned a slave. It is possible that the Simpsons were opposed to slavery on principle, for many of their contemporaries found the practice objectionable. It is more likely however that the eighteenth century Simpsons did not own slaves in Maryland or North Carolina because they were too poor. They were too poor to acquire large plantations and they were too poor to buy the slaves that were an essential component of the export economy. While they may have been too poor to acquire slaves, the Simpson family, relying on family labor, had prospered over three generations as middling farmers in Guilford and Rockingham Counties, North Carolina.

Thomas Simpson was 65 years old in 1804 when he began to prepare to move over the mountains to Middle Tennessee where it appears that his older sons Richard and Peter Ryan as well as his son-in-law Daniel Gough, all neighbors in Rockingham County, had preceded him. On May 31, 1804, Thomas Simpson sold an 101 acre parcel on Jacobs Creek to his brother-in-law and neighbor Thomas Knight for 100 pounds. The property is described as “waters of Jacobs Creek-beginning at black oak Thomas Knight’s corner” with neighbors including Rowland Williams, Jacob Periman and Charles Bruce.170 The land sold in 1804, although it was adjacent to property of Charles Bruce from whom he had purchased 150 acres in 1792, does not appear to have been the same property.171

At some other time, Thomas Simpson sold 50 acres on Brushy Fork of Jacobs Creek to Mary Patrick, whose family had owned Patrick’s Mill near the Simpson family properties at Mears Fork. It is unclear where the Brushy Fork property was located or why or when it was sold. Like many land transactions of the time, the sale of the Brushy Creek property remained unrecorded until 1807 when the estate of Mary Patrick sold the property.172 There is no record that Thomas Simpson sold the 150 acre parcel he owned but he may have transferred ownership, without recording the deed, to his son Nathaniel who continued to live in Rockingham County until at least 1830.173 Also preparing to move to Tennessee, Peter Ryan Simpson sold the 106 acres he had purchased from Adam and Allafa Trollinger in 1796 to Thomas Trollinger for $150 in November 1804.174

Sometime after the 1804 sale of his North Carolina property, Thomas Simpson, a he had fifty years earlier, loaded the wagons to move to a new frontier. Accompanied by his wife Mary Knight Simpson and their four children, he traveled over the mountains into Middle Tennessee. Leaving only his adult son Nathaniel in Rockingham County, Thomas Simpson and his family were in the early part of a vast migration from North Carolina that would continue for nearly fifty years. Between 1815 and 1850, one-third of the residents of North Carolina, like Thomas Simpson and his family in 1804, migrated to other states.175

Although North Carolina residents had claimed more than five million acres in Tennessee, including 2.8 million acres granted to veterans of the Revolutionary War, Thomas Simpson was not among those who had acquired Tennessee land while living in North Carolina.176 The Third Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse in 1805 had extinguished Cherokee land title in central Tennessee. The Thomas Simpson family settled on the former Indian lands on the highland rim of the Cumberland Plateau. In 1807, the area was organized as Warren County. Within twenty years, the Thomas Simpson family, swollen with grandchildren and in-laws, would again be loading the wagons for a move to the new lands available in the Boonslick region of central Missouri.177