12/26/1714 – 5/1795

From the notes of Kirke Wilson, May, 1991.

Richard Simpson (1714-1795) m. Elizabeth Reese (?) m. #2 Mary name unknown from both marriages, 3 sons and 3 daughters 1739-c 1760 first child, Thomas b. 23 Sep 1739, Old Baltimore Co, Md.

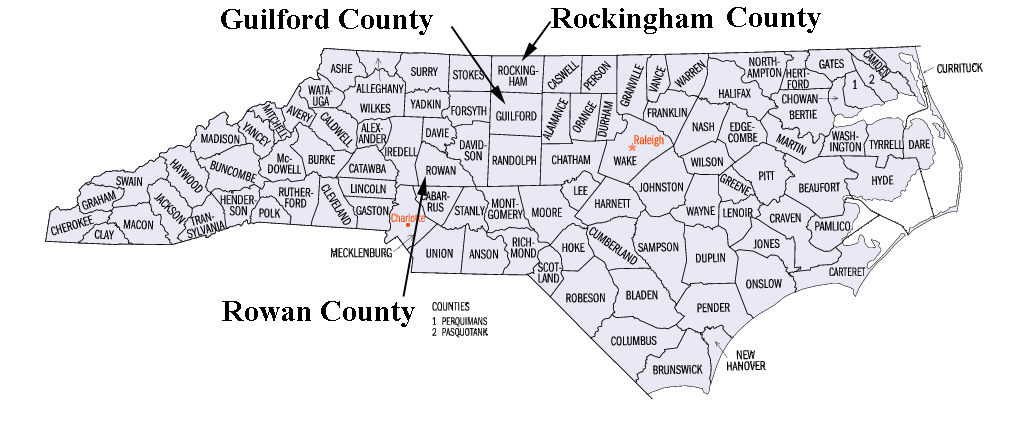

With others, Richard Simpson family moved from Maryland to North Carolina (Rowan Co; Guilford Co; Rockingham County-Upper Haw River area) during late 1750s.

The following was copied from pages 10 through 17 of ” A VERY

IMPROVING STATE: THE SIMPSON FAMILY IN NORTH CAROLINA, 1755 – 1804″, by Kirke Wilson, 1995.

The Richard Simpson Family in North Carolina:

Sometime in the 1750s, the second Richard Simpson (1714-1795) moved with his family from Maryland to North Carolina. It is likely that he delayed the move until the fall of the year when he had completed harvesting his crops and had disposed of his property. He loaded his family and possessions in a wagon and followed the Great Wagon Road south bringing livestock, seed, farming equipment and the supplies necessary to survive the winter and begin farming in the spring. By then in his 40s with six children, Richard Simpson settled in the Haw River area of Rowan County approximately thirteen miles north of what is now Greensboro, North Carolina.28 The Haw River is 130 miles long. It flows northeast through what is now Guilford County into Rockingham County before joining Deep River to form the Cape Fear River and flow into the Atlantic Ocean.

By May 1758, Richard Simpson had lived long enough in Rowan County to be summoned for service on the grand jury. The county seat at Salisbury was an 80 mile horseback ride, three days if the roads were dry, from his home. When he failed to appear, the county court ordered that he be fined along with six other county residents.29 In 1759, Richard Simpson paid taxes in Rowan County.30 In August 1764, he purchased 100 acres of land on the south side of Mears Fork in what was then Rowan County. Mears Fork is a tributary of the Haw River that flows northeast across Guilford County. Mears Fork follows a narrow valley that widens as it approaches the confluence with the Haw River near the present line separating Guilford and Rockingham Counties.31 Simpson paid twelve pounds North Carolina money to William Williams for land that Lord Granville had granted George Jurdan, Jr. in 1753.32 William Williams was a Haw River farmer who engaged in land transactions with various members of the Simpson family over a thirty-year period. He was not the William Williams who was a hatter and real estate speculator in Salisbury during the same period.

The Simpson land was the western and upstream part of a 320 acre parcel that Williams had acquired in 1758. The land was bounded on the north by Mears Fork and on the east by Line Branch. Williams continued to live on adjacent property east of Um Branch running to the mouth of Mears Fork at the Haw River.33 The land was located near the small Haw River bridge that today marks the boundary between Guilford County and Rockingham County. The property was immediately west of what was called Iron Works Road in the 18th century and is now Church Street Extension.34 Church Street begins in downtown Greensboro and runs north into Rockingham County through gently rolling hills of suburban housing, small farms, open fields and woods. The Mears Fork land is two miles north of Gethsemane United Methodist Church and the crossroads store at State Route 150 and two miles south of the village of Midway at the intersection of US 158 in Rockingham County.35 Mears Fork, Haw River and Troublesome Creek to the north are narrow streams, shaded by thick growth of vines and trees with little bottom land for cultivation. Since colonial times, these streams have offered little or no obstacle to traffic between the primary roads, like State Route 150 and US 158, that follow the flat ridges separating the many streams. Land is fertile red clay with crops planted on the gentle, upland slopes away from the streams.36

Richard Simpson and his family continued to live on the Mears Fork property foi thirty years. At some point after arriving in North Carolina, Elizabeth Simpson died and Richard Simpson remarried. His second wife, Mary, was the mother of Richard Simpson’s step-daughter Elizabeth, the wife of Cain Carroll who acquired 100 acres sout] of William Williams’ property in 1779.37 What little record survives suggests that Richard Simpson was a stable and respected figure. He and his sons acquired several parcels of land in the Mears Fork area over thirty years and Richard Simpson was asked by prominent neighbors, to assume responsibility in settling their affairs. In October 1765, Richard Simpson appeared in Rowan County Court as a witness in the probate of the estate of a prosperous neighbor, John Hallum, Sr.38 Hallum had obtained a Granville grant on a branch of Mears Fork in 1762 and owned 220 acres and one slave i the time of his death in 1764. 39

The following year, another Haw River neighbor died naming Richard Simpson co-executor of his estate and guardian of his children. David Rothera left his 320 acre homeplace and mill seat on Troublesome Creek to his youngest son David. Young David and his sister Rachel were the “two small children left to the care of Richard Simpson & his wife Mary.” In his 1765 will, the father also provided for the “schooling” of the two Rothera children for whom the Simpsons were guardians. 40

For the next thirty years, Richard Simpson farmed with his family on the Mears Fork property. Like others on the frontier, he earned money in every possible way including, on one occasion, as a bounty hunter. In 1765, he was one of 110 Rowan County residents filing claims for “woolfs, panthers and cats” they had killed. In addition to bounty claims totalling 289 pounds, residents sought reimbursement for other services provided the county including “making a pillory…repairing the goal (sic) & Irons, etc.”41 The Rowan County Court set the tax rate at one shilling, six pence proclamation money on each of the estimated 2800 taxables in the county. Suffering from the uncollected taxes that, in subsequent years, would be part of the tax protest of the Regulators’ Revolt, the Rowan County Court,

Order’d that, the dark pay unto the persons mentioned to have claims on the County for the, Year-1764, four-Fifths of their claims Only as he has no more money in his hands, by reason of the delinquent Taxes for that year.42

For his claim of one wolf killed, Richard Simpson received a partial bounty payment of twelve shillings.43

Although they were young adults, Richard Simpson’s three sons continued to live with or near their father on Mears Fork. In 1768, when the Rowan County Court ordered taxes collected, Thomas Donnell, the Justice for the Haw River area of the county, reported 254 titheables subject to taxation including eighteen slaves. Donnell reported that Richard Simpson, Senior and Samuel Marshall, presumably a hired man, were living at one location and that the three sons, Thomas, Richard, Jr. and Nathaniel were living nearby, perhaps on adjacent properties. None of the four Simpsons owned slaves. In addition to the four Simpsons, Haw River residents in 1768 included the Reverend David Caldwell, a Princeton-trained Presbyterian minister, as well as William Williams, Thomas Knight and William Moorland.44 The Simpson family engaged in several real estate transactions with Williams from 1759 to 1792 and members of the Simpson family married members of the Knight and Moorland families.

In addition to tax payments, colonial North Carolina also required adult males to perform voluntary service in the militia and the construction and maintenance of roads, bridges and other public works. Free males between the ages of 16 and 60, unless they were members of groups exempted by occupation, were obligated to participate in a regular schedule of musters. The frequency of North Carolina musters varied between 1760 and 1775. Captains were responsible for assembling local companies of approximately fifty men for “private” musters three to five times a year and colonels were responsible for the “public” muster of county regiments once or twice a year. Members of the militia were required to provide their own equipment including firearms, powder and shot. Musters included military drills as well as social events and attendance was enforced with fines of five and ten shillings.

Like the practice in 16th and 17th century England, men in colonial North Carolina were also required to provide labor in the construction and maintenance of public roads. Men were required to provide as much as one day a month in road service if it were needed, and were subject to fines of a day’s wage, two or three shillings, for failure to participate.45 In 1769, Richard Simpson was one of eleven Rowan County residents appointed to a “jury” with responsibility “to View and Lay off a Road from the Forks of Silver Creek Road to Sherrells Ford on the Catawba River.’146 Roads were a chronic problem in the North Carolina piedmont. They were poorly-designed, often little more than paths through the woods, and were inadequately maintained. They were often impassable due to boulders, fallen trees and flooding. The roads were rutted, often muddy and difficult to follow. An Act of 1764 required that roads be cleared of brush 21 feet wide with 12 foot wide bridges, mileposts and signposts at forks. The roads remained neglected and were an obstacle to the economic and social development of the piedmont well into the 19th century.47

The Mears Fork area of Rowan County became part of Guilford County in 1770.48 At some point, Richard Simpson, denoted “Esquire” in the county records, purchased land from someone named Southwell who had acquired the land from Lord Granville. By the end of 1773, the Simpson portion of the Southwell land had been sold William Nunn, Esquire, owned part of what had been the Simpson land and William Triplette sold another 100 acres for 100 pounds, one shilling to a buyer from York County, Pennsylvania.49 In 1777, William Nunn, Junior sold 519 acres, including his father’s home, to a buyer from Orange County for 400 pounds. This land is described a; being on High Rock Creek. Richard Simpson, presumably the former owner of part of the Nunn property, was a witness to the 1777 transaction.50 In 1779, Richard Simpson owned 150 acres on “Mares” Fork of Haw River adjacent to the northwest comer of property owned by Cain Carroll.51

In later years, two of Richard Simpson’s sons acquired adjacent properties on the south side of Mears Fork. Thomas Simpson bought land on the east side of his father in 1779 and south of his father in 1782. In 1783, the state of North Carolina granted 63 acres to Richard Simpson, Junior. The 63 acres was along the west side of the property his father had purchased in 1764.52 By 1785, Richard Simpson qualified for exemption from the poll tax, presumably based on his age. His exemption was approved by the Guilford County Court at the August 1785 session.53

Richard Simpson died sometime early in 1795 on the Mears Fork property he had owned since 1764. He left “all the land on which I now live” as well as two other parcels of twenty acres each to his third son Richard (c. 1748-1804). To his son Thomas, he left “one breeding sow & a chair” and to his son Nathaniel “a white mare”. To his three daughters and one step-daughter, Richard Simpson left household goods including a feather bed, trunk, chair, a stone quart mug, a spinning wheel and several basins including two of pewter. He specified that his supply of feathers “be equally divided” among his daughters. He also left property to his grandchildren including a three year old heifer to Elizabeth Rees Hicks, a chest to Elizabeth the daughter of his son Thomas and a “young cow named Rock” to Nathaniel, a son of Thomas. Four other grandsons, including Richard Simpson, a son of Thomas, shared the proceeds from the sale of the remainder of their grandfather’s personal property. His will, naming his sons Thomas and Richard as executors, was admitted for probate in Guilford County in May 1795.54

After nearly forty years on the North Carolina frontier, Richard Simpson had successfully acquired real estate and personal property and, with his wives, raised a large family. He had been a pioneer who had settled land and prospered as a farmer despite the political and social turbulence of the Carolina frontier during the colonial and revolutionary period. He appears to have gained the respect of his neighbors and was asked to administer their estates and assume responsibility for their children. Although a few of his neighbors owned slaves, there is no record that Richard Simpson owned slaves at any time during his forty years in North Carolina. The Regulator rebellion was active in Guilford County but there is no evidence that Richard Simpson participated. By the time of the Revolution, he would have been too old for militia duty but lived in an area that was crossed repeatedly by Continental troops fleeing the British and then returning to fight the Battle of Guilford Court House. The Haw River area was used by the Continental Army and state militia as a staging area before the battle and as a place of rest and recovery after the battle. Although there is no direct evidence, it is likely that the Simpson family and their neighbors were called upon to provide whatever grain and meat they could to supply the Continental army camped at Troublesome Creek.