FOR WE CANNOT TARRY HERE:

THE COOPER AND SIMPSON FAMILIES ON THE FRONTIER

Kirke Wilson San Francisco 1990

For my father, Earl Simpson Wilson, and those Coopers, Simpsons and others whose courage and strength inspire the generations who follow.

For we cannot tarry here, We must march my darlings,

We must bear the brunt of danger, We the youthful sinewy races,

All the rest on us depend, Pioneers! 0 Pioneers!

Walt Whitman

“Song of the Pioneer,” 1865

Onward ever, Lovely river,

Softly calling to the sea, Time that scars us, Maims and mars us,

Leaves no track or trench on thee.

SamuelL Simpson “Beautiful Willamette,” 1868

History abhors determinism but cannot tolerate chance. Why did we become what we are and not something else?

Bernard do Voto, preface to The Course of Empire, 1952

So it is with a family. We carry dead generations with us and pass them on to the future aboard our children. This keeps the people of the past alive long after we have taken them to the churchyard.

Russell Baker

The Good Times, 1989

PART I

THE VIRGINIA, KENTUCKY,

TENNESSEE FRONTIER, 1750-1800

Chapter 1: The Early Frontier 1

Chapter 2: The Frontier Before the Revolutionary War, 1763-1775 24

Chapter 3: The Revolution, 1765-1781 41

Chapter 4: The Revolutionary War on the Frontier 53

Chapter 5: Kentucky in 1782 79

Chapter 6: Life on the Tennessee Frontier 1782-1800 103

Afterward 135

Index 136

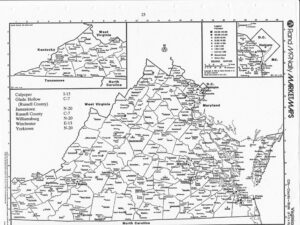

Maps

Virginia 23

Tennessee 40

Kentucky 78

PREFACE

What follows is the first draft of part of the story of the Simpson family for which I have been collecting information for several years. My interest began as a genealogical investigation simply trying to identify ancestors and plot their travels. As I accumulated more information, I became increasingly interested in how these people lived and why they kept moving. My focus shifted from them to the circumstances in which they lived and I began to realize that their story, the story of common people raising families in uncommon times and settings, might illuminate that part of United States history related to the frontier. The brief family history which I had intended had grown to a broader effort to understand the settlement of the West through the experience of this restless but ordinary family and hundreds of families like them who uprooted themselves repeatedly in the nineteenth century and moved west.

When completed, the story will consist of five sections each comprising several chapters. The first part, which is enclosed, includes the period from the early exploration and settlement of Kentucky and Tennessee in the late eighteenth century. The second part, much of which has been completed, is devoted to the Missouri frontier from 1800 to 1846 and includes chapters on the War of 1812, the fur trade and the Santa Fe Trail. In future years, a third part will follow members of the Cooper and Simpson families across the plains to California and Oregon in 1846. The fourth part will include chapters on the Oregon period 1846 to 1900 including the Cayuse War, the anti missionary Baptists of William Simpson, the peregrinations of Benjamin Simpson in business, politics and Indian affairs, the activities of Sylvester Simpson as legal scholar and education leader as well as a chapter on Samuel Simpson, the pioneer poet. A fifth part will describe the activities and experiences in California of the Coopers and Simpsons during the last decades of the nineteenth century as the frontier closed.

Throughout the story, I will be using the context of the time and place, as best I can describe it from primary and secondary sources, as a frame within which we can picture these families and their lives. Much of the story takes place on the frontier where literacy is limited and documentation is scarce. During the early period there is little direct documentation of the Cooper and Simpson families except as they participate in wars or buy land. As the story moves west into Missouri and Oregon, the trail becomes rich with letters, contemporaneous recollection and official records. Despite the information available about the families, the places and the times, significant aspects of these pioneer lives are missing. The major gaps are in the everyday lives of the people including particularly the lives of the women and the life in the home. The story follows the families who moved and neglects those Coopers and Simpsons who remained in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee and Missouri. I am hoping that this preliminary draft will solicit comment and information about sources I may have overlooked and documents of which I am unaware.

Like anyone who inquires about frontier history, I am deeply indebted to the tireless historians of the 19th century, particularly Lyman Copeland Draper and Hubert Howe Bancroft, who preserved the information on which other historians depend by collecting the documents and interviewing the pioneers. I also found myself depending on the work of a group of regional and local historians of the 19th century, many of them anonymous, who had prepared histories at the time of the national centennial in 1876. I am particularly grateful for the assistance and access to historical collections I received at libraries throughout the United States including the Bancroft and Doe Libraries of the University of California, the Boonslick Regional Library in Boonville, Missouri, the California Historical Society, the Culpeper Town and Country Library in Virginia, the Filson ” Club in Louisville, the Joint Collection University of Missouri Western Historical Manuscript Collection – Columbia and the State Historical Society of Missouri Manuscripts, the Library of Congress, the National Park Service, the New Mexico State Historical Society in Santa Fe, the New York Public Library, the Oregon Historical Society, the Oregon State Archives in Salem, the San Francisco Public Library, the Tennessee State Library and Archives in Nashville, the Transylvania University Library in Lexington, Kentucky, the United States Archives in Washington, D.C., the Wisconsin State Historical Society and the Coe Collection of Western Americana and the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University.

Like other contemporaries who have written about the Simpsons, I am the beneficiary of a serendipitous contact with my remote cousin C. Melvin Bliven of Wedderburn, Oregon and his generosity which, among other things, led me to Sam L Simpson’s 1981 book Five Couples and Shirlie Simpson’s 1982 book, The Ore2on Pioneer: Benjamin Simpson and his Wife Nancy Cooper.

My brother Bruce Wilson and my cousin Kevin Wilson have been very helpful in bringing obscure sources to my attention and exceedingly patient in awaiting any product.

San Francisco, California

June 1990

lV

INTRODUCTION

The Simpson families who crossed the plains to Oregon by wagon in 1846 were descended from pioneer families who had lived on the frontier since before the Revolutionary War. From the frontier of Virginia, they were early settlers in Tennessee, Kentucky and Missouri. They had fought Indians and British to claim lands which they cleared, settled and farmed before moving on to new opportunities on a new frontier. Members of these families fought in the French and Indian War and Lord Dunmore’s War while in Virginia, the Revolutionary War and subsequent Indian campaigns while in Kentucky, and the War of 1812 while in Missouri before moving to Oregon where they participated in the Cayuse Indian War.

Members of these families were among the first settlers in Kentucky and Tennessee at the time of the Revolutionary War and among the first settlers in Missouri before the War of 1812. They were among the first parties to successfully travel the Santa Fe Trail and among the first parties to use the Barlow Road across the mountains into the Willamette Valley of Oregon. They were elected to public office in the frontier settlements of Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri and Oregon and were active in the civic and spiritual life of the frontier. These families, named Simpson, Cooper, Kimsey, Higgins, Knight and Smelser, built homes, planted crops and raised chicken on the frontier while continually moving west.

For these pioneers, the frontier was the opportunity to begin anew and the hope they would do better. It was the attraction of cheap land, cheap if you were prepared to invest the effort to clear it and protect it from Indians, and it was the chance that the new land might produce greater prosperity than the old. After frequent moves in each generation, the lure of the new frontier may have simply been the product of recurring dissatisfaction or restless habit.

The idea of the frontier was a significant factor in the American imagination from the early days before the distinguished historian Frederick Jackson Turner pointed out its critical role in American history and social development a century ago. The historical pattern was obvious. The country began along the rugged coast of New England and in the fertile lowlands of Virginia and, as the population expanded, pioneers pushed forward into the wilderness and often into serious political disagreements with foreign countries, Indians or even other parts of our own country over land claims and settlement rights. In nearly every case, the pioneers eventually prevailed, the frontier became settled and opportunities lay out on another new frontier where the pattern would be repeated. This history built the country westward, over the first mountains with Daniel Boone, into the great valleys of the midwest and finally across the plains with the wagon trains.

For much of the past hundred years, historians have debated Turner’s frontier hypothesis. Some have modified or elaborated the thesis while others, including particularly a new generation of young scholars, have vigorously challenged Turner’s formulation. There is little quarrel with the notion that the wilderness created opportunity and required the remaking of democratic institutions out of chaos. The central issue is whether this process of taming the wilderness and settling the frontier resulted in something unique called the American character, that somehow European sophistication was stripped off by primitive simplicity. As critics have pointed out, this romantic view, with its own primitive simplicity, is too grand to reflect the diversity of frontier experience and neglects the frontier roles of women, Indians, traders, trappers and others who fall outside the Daniel Boone archetype. Any contemporary analysis of the frontier experience requires a more complex view of the contributions of those whose history has been neglected and somewhat greater humility about the morality of a process in which Europeans systematically grabbed land from Indians through lies, trickery, force and threat, always resulting in treaties of purchase which were being violated as the ink dried.

As the Cooper-Simpson narrative suggests, the interaction of settler and Indian was formative seems to be somewhat in conflict with the myth of the independent and self-reliant frontiersman. Like his contemporary counterpart, the frontier entrepreneur saw government as an ally in the achievement of private advantage.

If the frontier hero was far too human and far less independent than the myth, what remains of Turner’s notion that the frontier experience contributed somehow to the creation of national character? If that national character is the mix of optimism, independence and willingness to build anew, the myth of the frontier experience may have been far more powerful than the reality of that experience. Whether it was the availability of relatively unclaimed land or the relative absence of traditional social and institutional constraints; the frontier was briefly a place of hope and opportunity. It was also a place where individual effort and risk might be rewarded and where for a time, people might be judged on their own accomplishments rather than the social status of their families. Finally, the frontier was a place where individuals, seeking personal advantage, acted with confidence that they were also advancing the welfare of their communities and nation.

Much of this jumbled 19th century concept of the national character survives. Some of it remains only a myth. Other parts, particularly the optimism and independence, while not necessarily part of some national character, are essential parts of the national myth. They remain powerful, however we may stray, because they provide a unifying sense of national purpose and national ideals. While a relatively small part of the current United States population has any direct claim to the frontier experience, much of the population, including many of the most recent immigrants, deeply and strongly believe the myth and shares its values of independence and optimism. It may be mostly myth but it may also be central to those values, experiences, expectations and mannerisms which unite us as people and set us apart from others.

CHAPTER ONE

THE EARLY FRONTIER

As for the West… the limits are unknowne.

Captain John Smith 1624 1

The western limits of Virginia were indeed “unknowne” to Captain John Smith and the 100 men and four boys who perched precariously on the Chesapeake Bay shore at Jamestown in 1607. Smith and his companions were promptly attacked by Indians and weakened by disease and starvation. Fifty-one died during the first six months, but they would survive to build the first permanent, English-speaking colony on the North American continent. While the western limits were unknown to the British, they were well-known to the Spaniards. The Spaniards had established colonies in the Caribbean soon after Columbus and explored the southern half of what is now the United States during the sixteenth century while the British remained at sea searching for a mythical passage to the East.

The Spaniards settled Hispaniola Island, now known as Santo Domingo, in 1492, Puerto Rico in 1501, Jamaica in 1510 and Cuba in 1512. Hernan Cortes, with about 500 soldiers, conquered the Aztec Empire 1519 to 1521 and claimed Mexico for the Spanish Empire. Within fifteen years, the Spaniards had completed the conquest of the Inca in Peru and the Chibcha in Columbia. Other Spaniards explored the New World by sea and on foot. Juan Ponce de Leon explored the Florida peninsula in 1513 and Alonso Alvarez de Pineda explored the Gulf Coast in 1519. Panfilo de Narvaez died exploring Florida in 1528 and his colleague Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca spent the next eight years crossing Texas and Mexico to the Pacific (1528-1536).2

Hernando de Soto organized an expedition that spent four years exploring what is now the ten states of the southeastern United States (1539-1543) while Friar Marcos de Niza (1539) and Francisco Vasquez de Coronado (1540-1542) were exploring the Southwest including parts of what is now Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. Coronado’s army of ambitious second sons of Spain ranged from the Colorado River through the pueblos of the Zuni and the Hopi to the Indian villages of central Kansas. In the summer of 1540, Coronado’s scouting parties included the first Europeans to see the Grand Canyon in Arizona, the Colorado River along what is now the California-Arizona border and the vast herds of bison on the plains. The following year, while returning to New Mexico from Kansas, Coronado’s small army was guided along an old Indian trade route which 280 years later would become the Santa Fe Trail.3

While the Spaniards explored much of what is now the southern half of the United States during the first half of the sixteenth century, they were slow to establish permanent settlements like those in Mexico and South America. The first Spanish colonies in Florida (1559-1561 and 1566- 1576) were unsuccessful and were abandoned. The French, in a bold move to challenge Spanish hegemony in the region, attempted to establish colonies in Florida in 1562 and 1563. The first French attempt failed and the second was wiped out by the Spaniards in 1565. The same year, the Spaniards established St. Augustine, the first European settlement to survive in what is now the United States. During the following decades, the Spaniards established fortified outposts and missions along the Florida-Georgia-Carolina coast and across northern Florida. Seventy years after the Fray Marcos expedition, the Spaniards established a permanent settlement at Santa Fe in 1609.

British exploration of North America began in 1497 when John Cabot (nee Giovanni Caboto), a Genoese in British service, landed briefly in what was probably Newfoundland. After this early start, the British were inactive in the New World for more than half a century until Elizabeth I became queen in 1558 and the British began to assert their sea power. Sir John Hawkins, Sir Francis Drake and Sir Humfrey Gilbert all sailed the coasts of the New World for their queen. Drake interrupted his around-the-world buccaneering expedition (1577-1580) in June 1579 to land on the California coast where he left a plate of brass and claimed the land he called Albion “…in the name and to the use of Her Most Excellent Majesty.”4

3

Sir Humfrey Gilbert sailed to Newfoundland in 1583 and his half-brother Sir Walter Raleigh sent ships to the coast of what is now North Carolina in 1584 and 1585 to assess the prospects for colonization. In 1587, Raleigh sent 117 men, women and children to establish a permanent British settlement at Roanoke Island on the coast of what is now North Carolina. The supply ships that were to have been sent to Roanoke in 1588 were diverted to the battle with the Spanish Armada. By 1590, when the first British ships arrived to resupply the stranded colonists, there were no survivors. The members of the “Lost Colony” had either starved or been killed by Indians.5 ..

The Virginia Frontier

In 1606 investors in London and Plymouth each formed joint-stock companies to establish colonies in Virginia. The Virginia Company of London sent out three small ships and landed 104 settlers on the Virginia tidewater at Jamestown. The colony was weakened by disease and starvation and attacked by Indians. Timely reinforcements in 1609 forestalled plans to abandon the little settlement. The colonists planted gardens to feed themselves and experimented with several export crops including silkworms, flax and hemp. In 1612, they discovered that the Virginia lowlands were particularly well suited to the cultivation of tobacco. With an export crop and source of income, the growth of the colony was assured. By 1618, immigration had increased the population of the Virginia colony to 1000 and the settlers were beginning to spread out along the James River seeking fertile soil for tobacco.

The Virginia colonists, after early skirmishes, lived peacefully with their Indian neighbors for more than a decade. The unsuspecting settlers were shocked one March morning in 1622 when the Indians mounted coordinated attacks at eighty separate locations along a 140 mile line. The Indians were unsuccessful in driving the colonists into the sea but they killed 347 of the 1240 settlers in Virginia. The surviving colonists consolidated the settlements, strengthened their defenses and organized retaliatory raids against the Indians burning houses and destroying food. In spite of the threat of Indians and continuing problems of disease, the Virginia colony continued to attract immigrants from England. The population reached 3,000 by 1630 and 8,000 by 1640.

In April 1644, the Indians launched a second general attack on the Virginia settlements killing between 400 and 500 colonists. The settlers organized punitive raids which resulted in a 1646 agreement with the Indians. Starting a pattern that would continue across the continent for more than 200 years, the Indians gave up land to the colonists in exchange for assurances that other land would be reserved for Indian use. The Indians of Virginia ceded the Tidewater lands between the York and James Rivers for the English and obtained English recognition of Indian rights to live and hunt without interference in the lands north of the York River.6

As the Virginia population grew, the settled area expanded until it reached the “fall line” where rapids and falls prevented coastal vessels from travelling upstream. This line, dividing the settled coastal plane called the Tidewater, from the upland wilderness called the Piedmont, was the Virginia frontier in the last quarter of the seventeenth century. The line also divided the large and slave-dependent tobacco plantations from the frontier farms, many of them owned by families who had served out indentures in the Tidewater.

A frontier Indian incident in 1676 resulted in what has been remembered as Bacon’s Rebellion and demonstrated the independence of the frontier settlers as well as the intransigence of the British governor. A dispute over payments due Indians resulted in the murder of a farmer and escalated into a border war. The settlers retaliated with a campaign against the Indians and the murder of five Susquehannock chiefs under a flag of truce. The Indians responded with raids killing 36 frontier settlers.

5

When the royal governor Sir William Berkeley (1606-1677) vacillated in his response, the frontiersman defied the governor and formed an army under the command of Nathaniel Bacon, Jr. (1647-1676), a recently-arrived, young planter who was a cousin of the governor’s wife. Rather than accept the governor’s proposal of a defensive strategy, the angry frontiersmen attacked and defeated the Indians in two engagements. Bacon’s army turned on Governor Berkeley who fled to safety on the eastern shore of Chesapeake Bay. Bacon’s army burned Jamestown but disintegrated in the fall and winter of 1676 after Bacon died of disease. Governor Berkeley returned and reasserted his authority by hanging 23 leaders and repealing laws enacted during the rebellion.7

During this period, Virginia tested a variety of methods to protect the frontier settlement against the Indians who had been pushed out of the tidewater. Although the settlers were serving as a buffer to protect the tidewater plantations, the planters were reluctant to allocate money for frontier defense. After the Indian uprising in 1675 and 1676, the Virginia Assembly proposed the assignment of troops to a string of forts located along the fall line. The settlers objected to the fort strategy because it was too passive and too costly. In 1691, the Assembly suggested a second approach deploying mounted rangers to scout for Indians along the fall line.

By 1701, Virginia found an effective but inexpensive solution by offering to subsidize frontier settlement. Virginia offered land grants of 10,000 acres or more, along with exemption from taxes and other military service as well as twenty-year exemption from quitrents for those communities providing, for every 500 acres,

one christian man between sixteen and sixty years of age perfect of limb, able and fitt for service who shall alsoe be continually provided with a well fixed musquett or fuzee, a good pistoll, s.harp simeter, tomahawk…8

In addition to providing soldiers to protect the frontier, the new colonists were required to build forts within two years:

6

with good sound pallisadoes at least thirteen foot long and six inches diameter in the middle of the length thereof,and set double and at least three foot within the ground.9

These frontier forts in Virginia with their wooden stockades and militia were the model for the frontier stations in Kentucky in the 1770s and 1780s and the family forts of the Missouri frontier of 1810. The strategy of forts and militia enabled Virginia to push the settlements forward into Indian country.

In a strangely perverse way, the interaction with the Indians may have been the formative factor in frontier life. The constant threat of Indian raids required that the independent and self sufficient frontier family could not survive alone. Families would have to organize their lives with fortified stockades and militia to protect themselves and their neighbors. The massacres of 1622 and 1644 convinced the Virginians to settle in clusters and protect themselves. A frontier Indian incident in 1675 resulted in Bacon’s Rebellion, the first organized and armed defiance of British authority by colonists in North America. The pattern of frontier forts and militia, developed in response to the seventeenth century Indian threat in Virginia, became the model for Kentucky and Tennessee in the eighteenth century and Missouri in the nineteenth century. The organization and cooperation that was essential for frontier survival also provided the basis for self-government as the newly-settled areas matured.

Culpeper County

By the mid-eighteenth century, the western frontier of Virginia had advanced to the base of the Blue Ridge. The Shire of York, which dated from 1634, had been subdivided repeatedly into counties over the following century. Orange County, formed out of part of Spottsylvania County in 1734, was itself divided in May 1749. The area south of the Rapidan River, then called the Conway, remained in Orange County,

all that other part thereof, on the north side the said Rappahannock and Conway river commonly called the Fork of Rappahannock River, shall be one other distinct County and called and known by the Name of Culpeper County.10

The area bounded by the Rapidan on the South, the Rappahannock on the North and the Blue Ridge on the West became Culpeper County.11

The new county was named for Thomas Lord Culpeper, second Baron Thoresway (1639- 1689) who had served as Governor of Virginia from 1677 to 1683. Culpeper was the son of one of seven men who were rewarded for remaining loyal to the Stuarts after the execution of King Charles in 1649. The seven accompanied the Prince of Wales into exile in France where, in prolix gratitude,

Charles the Second by the grace of God King of England, Scotland and Ireland Defender of the faith…wee have taken into Our Royall Consideracon the great propagation of the Christian faith together with the wellfare of multitudes of Our Loyall Subjects by the vndertakings and vigorous prosecution of Plantations in fforeign parts, and particularly in our Dominions of America 12

he granted the seven 1.5 million acres of land in North America. The land was described by the king’s patent as,

lying in America, and bounded by, and within the heads of Tappahannocke als Rappahannocke and Quircough orPatawomecke Rivers, the Courses of the said Rivers and Chesapayoake Bay

13

Known as the Northern Neck of Virginia, the royal grant included all the lands lying between the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers from Chesapeake Bay to the “heads” of the rivers. Charles II was restored to the throne of England in 1660 and he confirmed the 1649 grant in September 1661. By 1681, Thomas Lord Culpeper had successfully acquired all but one of the shares from heirs of other patentees. When Culpeper’s widow inherited the missing share in 1695, the Northern Neck proprietary was owned in its entirety by the Culpeper family.

Richard (King) Carter, a prosperous Virginia planter acting as resident agent for the proprietors, was able to expand the proprietary to 5.3 million acres by extending claims over the Blue Ridge to the Alleghenies encompassing what is now 24 counties in Virginia and West Virginia including the county posthumously named for Lord Culpeper. Thomas, sixth Lord Fairfax, Baron of Cameron (1692-1781), the second Lord Culpeper’s grandson, inherited the vast Culpeper lands which came to be called the Fairfax proprietary.14

St. Mark’s Parish, organized in 1731, was located in that part of Orange County which became Culpeper County in 1749. Until 1752, when Bromfield Parish was established, all of Culpeper County was in St. Mark’s Parish. In later years, additional counties were formed out of the original Culpeper County. In 1793, the western part of Culpeper County became the new Madison County and in 1833, the northwest part of Culpeper County was organized as Rappahannock County.15

At the same time that Culpeper County was being formed, the Cooper family was beginning to leave a record in county life.16 On August 23, 1749, Lord Fairfax granted 400 acres of Culpeper County land to John Cooper.17 In March 1750, John J. Cooper was a witness to a land transaction in which Anthony Scott gave 105 acres of land to his daughter Elizabeth and her husband Thomas Corbin. 18 In May 1750, John Smith sold part of his land on the north side of the north branch of Gourd Vine River to Abraham Cooper, a carpenter, for 25 pounds.19 In November 1750, John Cooper and his wife Judith traded 300 acres of the Fairfax land to John Smith in exchange for 300 acres on the south side of the north fork of the Gourd Vine River. The land on the Gourd Vine was adjacent to a line separating the property of John Smith and Abraham Cooper.20

In September 1752, Abraham Cooper was a witness when Anthony Scott gave 80 acres to his grandson Richard Burke.21 When Anthony Scott died in 1764, his will left his books to his son and his plantation and lands to his wife Jane. In the event that Jane Scott died, remarried or left the plantation, the son was to inherit the land and Scott’s daughter Frances, the wife of Abraham Cooper, was to inherit other property. Each of Scott’s two other daughters received one shilling. Francis Cooper was a witness when Anthony Scott’s will was admitted to probate in 1764.22 It is unclear how John and Judith Cooper, Abraham and Frances Cooper and Francis Cooper are related except that they were landowners in the same Gourd Vine River area of north-central Culpeper County and were involved in business dealings with Abraham Cooper’s father-in-law Anthony Scott during the 1750s.

Francis Cooper and his wife, whose name is not known, established a household in Culpeper County in the early 1750s. In January 1756, Francis Cooper’s wife gave birth to their first son Benjamin A Cooper (1756-1841).23 Later that year, Francis Cooper served in the Culpeper County militia. He was one of 53 foot soldiers in the company formed in March 1756 under the command of Lt. Col. William Russell and Capt. William Brown.24 Francis Cooper served 95 days with the Culpeper troops defending the Virginia frontier during the French and Indian War.25

In May 1761, Francis Cooper purchased land in Culpeper County from John and Elizabeth McQueen for 30 pounds. The land was in St. Mark’s Parish and was located “on a stoney point corner to Richard Tutt, Gent. in John Yancey’s line…in Alexander McQueen’s line…”26 In addition to their oldest son Benjamin, Francis Cooper and his wife had several other children including a son Sarshel (1763-1815), as well as at least two other sons and several daughters including one named Betty, who married James Wood.27 Francis Cooper continued to live in Culpeper County until the Revolutionary War and served in Lord Dunmore’s War in 1774.

During this period, Culpeper County had a small number of large plantations, like the 20,000 acres owned by Robert Beverly and the 13,000 acres of Capt. John Strother, and a large number of small and medium-sized farms. In 1764, there were 63 plantations exceeding 1,000 acres and more than 700 farms between 100 and 400 acres. The smaller farms had a log farm house, typically sixteen by twenty feet with a gable roof, surrounded by fields, pastures, orchards and wooded areas. Since plows were not available until late in the eighteenth century, the Culpeper farmer of this period used hoes and other hand tools to grow corn, winter and summer wheat and tobacco. Crops were grown among the stumps of recently-cleared woods and rotated between grains and pasture as land-productivity declined. The large land owners, using slave labor, planted tobacco and allowed fields to lay fallow when productivity declined.28

French and Indian War

French claims in North America were based on the explorations of Giovanni de Verrazano, a Florentine working for the French king. Verrazano explored the Atlantic coast in 1524 and Jacques Cartier sailed up the St. Lawrence River in 1535-1536. From 1608, when they established an outpost at Quebec, the French had a strong interest in the interior of the North American continent. In 1673, Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette traveled down the Mississippi River to the Arkansas. Nine years later, Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle explored the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico. In April 1682, La Salle claimed the vast area drained by the Mississippi River,

In the name of the most high, mighty, invincible, and victorious Prince, Louis the Great, by the grace of God, King of France and of Navarre, Fourteenth of that name…29

He was uncertain whether the river was Colbert or Mississippi but he called the land Louisiana. By the early part of the eighteenth century, the French had established outposts in the Illinois country at Kaskaskia, Cahokia and Vincennes as well as Gulf coast settlements at Biloxi (1699) and Mobile (1702).

While the French were exploring the North American interior and establishing remote outposts, they were also engaged in intermittent continental warfare with the British and other European countries for nearly a century. The wars of the Old World were named like hurricanes in the New World. The War of the League of Augsberg (1689-1697) was King William’s War, and the War of Spanish Succession (1702-1713) was Queen Anne’s War. The War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748) was known as King George’s War in North America. Each of the European wars was accompanied by frontier skirmishes in North America. In most cases, Indians under the direction of the French engaged the frontier settlers of the British.

In King William’s War, the French and their Indian allies raided the isolated farms along the frontier in Connecticut, Massachusetts and New Hampshire. In Queen Anne’s War, the French and Indian attacks in Maine resulted in the killing or capture of 160 farmers and their families and the placing of a bounty of 40 pounds on each Indian scalp. In February 1704, 250 Canadians and Indians attacked the frontier town of Deerfield, Massachusetts where fifty townspeople were killed, 111 captured and seventeen houses destroyed. Nearly half of the captured townspeople, most of them women and children, never returned. By King George’s War, forty years later, the British colonies in New England were stronger and better organized. The colonies sent 4000 troops to Cape Breton Island where the “Bastonais” captured the strongly-defended Louisbourg fortress after a siege of six weeks.30

By 1748, the population of the English colonies in North America had grown to 1.5 million. The pressures of population growth were pushing the colonists against the mountain barriers and into the Indian territory claimed by the French. After the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, the French remained in control of the interior wilderness. The French strengthened fortifications and their alliances with the Indians along the Appalachian frontier. At the same time, colonists along the Atlantic coast were looking for ways to establish land claims west of the mountains. In 1747, a group of Virginia venture capitalists formed the Ohio Company of Virginia and two years later obtained a grant of 200,000 acres of land between the Appalachian mountains and the Ohio River.

In 1754, a young George Washington (1732-1799) was sent ‘”‘.ith Virginia militia to build a fort at the Forks of the Ohio, present-day Pittsburgh, to protect the Virginia claims. Finding that the French had erected Fort Duquesne at the forks and controlled the area, Washington and his out numbered Virginians surrendered and were allowed to return to their homes over the mountains. The following year, the British dispatched Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock and two army regiments to capture the Forks of the Ohio. With 1500 regular soldiers and 1200 colonial militia, Braddock’s army cut a road over the mountains and through the wilderness. On July 9, 1755, the French and Indians surprised Braddock’s army on the Monongahela River seven miles from the fort. The British and their provincial allies were decisively defeated in a battle in which Braddock was killed and 976 of his troops were killed or wounded.

The defeat of Braddock’s army, along with British failure to capture French forts at Crown Point and Niagara left the French and their Indian allies in unchallenged control of the wilderness and able to organize strikes at any point along the frontier. George Washington, who had served as a volunteer aide-de-camp to Braddock in the ill-fated campaign, wrote soon after the battle,

I tremble at the consequence that this defeat may have upon our back setters, who I suppose will all leave their habitation’s unless their are proper measures taken for their security.31

Col. James Innes, the commanding officer at a fort on the Virginia frontier, wrote an open letter, “I have this minute received the melancholy account of the Defeat of our Troops …it’s highly necessary to raise the Militia everywhere to defend the Frontiers.”32

Robert Dinwiddie, the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, anticipating a French and Indian invasion, called out the militia in three frontier counties and alerted the militia in nine adjacent counties. In August 1755, when the frontier militia proved ineffective, the Virginia General Assembly authorized a war tax and the formation of a Virginia regiment of 1200 troops to protect the frontier. Governor Dinwiddie appointed George Washington, then but twenty-three years old, Colonel of the Regiment and Commander-in-Chief of the militia.33 The precocious Commander-in Chief arrived on the frontier in September where he found that approximately 70 settlers had been killed in Indian raids. By October, the Indians had withdrawn and Washington was able to use the winter respite to construct four small forts along the 100 mile frontier in the Shenandoah Valley between the Blue Ridge and the Allegheny Mountains.34

In March 1756, Indians and their French allies resumed their attacks along the Virginia frontier. Pioneer families, who had been uprooted the previous summer, again abandoned their farms and moved into forts for protection. Realizing that the tiny Virginia Regiment was inadequate, Washington again appealed for assistance from the militia of nearby counties. In April 1756, Governor Dinwiddie, concerned about the possibility of a slave revolt, mobilized half the militia in the eleven Piedmont counties, a total force of 4000 including half the militia from Culpeper County. Dinwiddie wrote the militia commander in Orange County,

The Colo. of the Co’ty of Culpeper must take charge of the militia till a Co’ty Lieut. is appointed. I am well pleas’d y’t You took some Powder and Ball out of w’t I sent up, and I hope you will be able to supply Culpeper with some of it.35

While the Governor was calling out the militia, Washington was also requesting assistance from the nearby counties. He wrote Lord Fairfax,

I advise (if you have not already done it) you would send immediately to Culpeper, with Orders to raise and send such a number of men as you shall judge can be spared from thence; with such Arms, Ammunition, and provision as they can procure; for we are illy supplied with either here.36

Washington was disappointed when only fifteen men, some of them unfit for duty, arrived at Winchester by the appointed day.37

Two weeks later, still with no sign of the militia, the young colonel was becoming desperate.

He wrote the Governor,

Desolation and murder still increase, and no prospects of relief. The Blue Ridge is now our frontier, no men being left in this County except a few that keep close with a number of women and children in forts, which they have erected for the purpose. There are now no militia in this County; when there were, they could not be brought to action.38

Within days, the militia from nearby counties began to arrive on the frontier. The first troops appeared from Fairfax County on April 29 followed quickly by units from Prince William County and King George County.

By May 9, Col. Thomas Slaughter approached with 200 militiamen from Culpeper County, including presumably Lt. Col. William Russell’s company with Capt. William Brown and Francis Cooper.39 Washington, suddenly finding himself with more troops than he could use, ordered the Culpeper militia to stop on the road. According to information Washington had received, the Culpeper militia was poorly armed. He wrote, “they had not above 50 Firelocks in the whole.”40 Colonel Slaughter responded that, on the contrary, the 200 Culpeper troops had at least 80 guns.41 Within a few days, militia from three additional counties joined Washington’s troops at Winchester. As the Virginia militia assembled, the Indians who had been harassing the frontier vanished into the wilderness whence they had come.

Although the immediate Indian threat had abated, Washington knew that the calm was only temporary and that the Valley of Virginia could not be defended without fortifications and a reliable, disciplined militia. Instead of releasing the militia so they could return to their homes for spring planting, Washington decided to use the militia to build fortifications. Many members of the militia deserted while others refused orders. As Washington observed, the militia acted as though, they had “performed a sufficient tour of duty by marching to Winchester.”42 To improve morale, Washington increased the daily food ration for his troops from a pound of meat and pound of flour to a pound and a quarter of each and dismissed some of the most troublesome militia. To improve discipline and reduce desertion, Washington ordered the execution of a deserter and a Sergeant who had acted with cowardice in battle.43

The remaining militiamen, including much of the Culpeper militia, were assigned to building a chain of what eventually became 81 forts and blockhouses on the Virginia frontier.44 The militiamen from Culpeper were assigned to forts near Winchester for several weeks before being released to return to their homes in Culpeper County. A detachment of Culpeper militia under Capt. Williams Brown remained on the frontier through the winter of 1756-1757 and built a fort at Patterson’s Creek. For the next several years, Culpeper and adjacent counties sent militia each spring to strengthen the frontier in Winchester and Frederick County.45

The hostilities had been underway for two years before England declared war against France in 1756 for the fourth time in less than seventy years.46 As Francis Parkman described it, the French Governor in Canada “had turned loose his savages, red and white, along a frontier of 600 miles, to waste, bum, and murder at will.”47 In August 1758, Brig. Gen. John Forbes, with a slow-moving army of 6000, began building a wagon road over the mountains toward the French fort at the Forks of the Ohio. Forbes’ army, with George Washington as a division commander, ponderously advanced through the wilderness and captured a weakened Fort Duquesne in late November 1758.

Although the war began in the Ohio River Valley, the battleground shifted to Canada where, in 1758, the British captured French forts at both ends of the St. Lawrence River and defeated the French on the Plains of Abraham in 1759. The Treaty of Paris ending the war in 1763 resulted in British control of all of the area east of the Mississippi River and cession of the area west of the river, called Louisiana, to Spain.

The Proclamation Line of 1763

British victory in the Seven Year’s War, known as the French and Indian War in North America, assured that the wilderness between the colonies on the Atlantic seaboard and the Mississippi River, an area that had been under French control for nearly one hundred years, would now be under British jurisdiction. The British were uncertain about how to administer this interior wilderness of Indians, French traders and colonial land claims. The British received conflicting advice from those who wanted to maintain the wilderness and those who wanted to open the area to settlers or land speculators.

At the same time that Forbes and his army were building the wagon road that enabled the British to capture the Forks of the Ohio in 1758, George Croghan, a respected Indian trader, was representing the British in negotiations with Ohio Indians. In an effort to win the Indians to the British side, Croghan gave assurances, as part of the Treaty of Easton, that the British would reserve the lands west of the mountains for the Indians.48 In 1761, Col. Henry Bouquet, the British commander in the West, reassured the Indians about the wartime promise by issuing an unequivocal order that prohibited “…any of His Majesty’s subjects to Settle or Hunt to the West of the Alleghany Mountains on any Pretense Whatsoever.”49

The commitments that Croghan had made to the Indians in 1758 and Bouquet had confirmed in 1761 were given royal authority on October 7, 1763, when King George III issued a proclamation forbidding land grants, purchase of Indian lands or settlement west of the Appalachian mountains:

Whereas we have taken into our royal consideration the extensive and valuable acquisitions in America, secured to our Crown by the late definitive treaty of peace concluded at Paris…And we do further declare it to be our royal will and pleasure, for the present as aforesaid, to reserve under our sovereignty, protection and dominion, for the use of the said Indians…all the lands and territories lying to the westward of the sources of the rivers which fall into the sea from the west and northwest…all persons whatever, who have either willfully or inadvertently seated themselves upon any lands within the countries above described, or upon any other lands which, not having been ceded to or purchased by us, are still reserved to the said Indians, as aforesaid, forthwith to remove themselves from such settlements.so

The objective of the royal proclamation was to reassure the Indians while containing the colonists east of the mountains. It prohibited settlement or land purchase west of the mountains and required all western settlers to move east of the line. The boundary was a logical physical barrier. It was easily described and easily understood but it was inadequate to restrain those people in the colonies who had designs on the West.

George Washington, who had been exploring and claiming western lands for a decade, expressed the attitude of many colonists,

I can never look upon that proclamation in any other light (but I say this among ourselves) than as a temporary expedient to quiet the minds of the Indians and must fall of course in a few years especially when those Indians are consenting to our occupying their lands. Any person therefore who neglects the present opportunity ofhunting out good lands…will never regain it…51

Always cautious, Washington asked his agent to keep his opinion confidential, “I might be censured for the opinion I have given in respect to the King’s proclamation.”52 The Proclamation Line was frequently and broadly violated by settlers and land speculators. The British, although they had reduced their military presence in North America to save money, attempted to enforce the line. British soldiers forcibly evicted settlers west of the line, burning cabins and scattering livestock.

In 1768, the British and Iroquois met at Fort Stanwix to adjust the line. The British obtained land west of the mountains to the Ohio River from Fort Pitt to the Kanawha River. In exchange, the British agreed to retrocede lands occupied by the Iroquois east of the crest. The British paid the Iroquois 10,000 pounds for the lands west of the crest. The lands which the British bought from the Iroquois were occupied by the Shawnee, Delaware and Mingo, who were neither consulted nor compensated by either the British or the Iroquois. The Iroquois, as part of a strategic plan to direct the flow of settlement away from Iroquois lands, had offered to give up lands which the Iroquois claimed but did not use south of the Ohio River. The British accepted the limited cession while reaffirming the Proclamation Line along the frontier in the South.53 By 1768, 160 years after the first English colony in Virginia, the first pioneers were spilling over the natural and political barrier at the crest of the mountains.

Early Frontier Notes

1. Captain John Smith, The Generall Historie of Virginia. New England & The Summer Isles, Vol. I (Glasgow, 1907), p. 43, originally published 1624.

2. Dale Van Every points out that the Cabeza de Vaca expedition of 1528-1536 was the first to cross what is now the United States. The second crossing was by Lewis and Clark 269 years later. Dale Van Every, Ark of Empire (New York, 1963), p. 63n.

3. A Grove Day, Coronado’s Quest: The Discovety of the American Southwest (Honolulu, 1986).

4. Louis B. Wright and Elaine W. Fowler, editors, West and By North (New York, 1971),

p. 169, originally published 1628 in The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake. A “plate of brass” was discovered in Marin County, California in 1936 and is displayed by the Bancroft Library at the University of California. After extensive examination, the Bancroft Library has concluded that the “plate” is a clever twentieth century forgery and not Drake’s plate from 1579.

5. The exploration and settlement of North America is described in every survey of American history. The textbook The National Experience by John M. Blum and five other distinguished historians (New York, 1963) is among the best. The explorations and settlement of the frontier are recounted in Ray Allen Billington, Westward Expansion: A Histozy of the American Frontier (New York, 1967).

6. W. Stitt Robinson, The Southern Colonial Frontier. 1607-1763 (Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1979), pp. 22-50.

7. Ibid., pp. 61-65.

8. Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American Histozy (New York, 1921), p. 86.

9. Ibid.

10. Journal of the House of Burgess, May 10, 1749 in Eugene M. Schell, Culpeper: A Virginia County’s Histozy Through 1920 (Culpeper, 1982), p. 28.

11. John S. Hale, An Historical Atlas of Colonial Virginia (Verona, Virginia, 1978); Catherine Linsay Knorr, Marriages of Culpeper County. Virginia 1781-1815 (Pine Bluff, Arkansas, 1954). Culpeper, Virginia is 72 miles southwest of Washington, D.C. in the gently-rolling hills of the Virginia piedmont. From Washington, take I-66 west 33 miles to Gainsville and US 29 south 39 miles, through Warrenton to Culpeper.

12. Douglas Southall Freeman, George Washington: A Biography (New York, 1948), Volume I, Appendix 1-2, pp. 513-519. The original copy of the 1649 patent is Additional Charter 13585 in the British Museum.

13. Ibid. The seven original proprietors were Ralph Lord Hopton, Baron of Stratton; Henry Lord Germyn, Baron of St. Edmundsbury; John Lord Culpeper, Baron of Thoresway; Sir John Berkeley; Sir William Morton; Sir Dudley Wyatt; Thomas Culpeper, Esq.

14. Ibid., pp. 447-513. In a lengthy appendix to volume one of George Washington, Freeman reviews the history of the Northern Neck proprietary. The proprietary comprised most of what is now the Virginia counties of Alexandria, Clarke, Culpeper, Fairfax, Fauquier, Frederick, King George, Lancaster, Loudon, Madison, Northumberland, Page, Prince William, Richmond, Shenandoah, Stafford, Warren and Westmoreland as well as the West Virginia counties of Berkeley, Hardy, Jefferson and Morgan. Charles A Hanna, The Scotch Irish, Vol. II (Baltimore, 1968), p. 44. Raleigh Travers Green, Genealogical and Historical Notes on Culpeper County. Virginia (Baltimore, 1983), p. 1, originally published 1900, adds Hampton County but omits Alexandria, Clarke and Warren Counties.

15. Hale, Atlas of Colonial Virginia.

16. No earlier record has been found of the arrival of these Cooper families in North America. A century later, Cooper was the 26th most common surname in England. Because it is a “trade” name like Miller or Taylor, the Cooper name is not confined to any particular region of England. Hanna, The Scotch-Irish, Vol. II, p. 420.

17. John Frederick Dorman, compiler, Culpeper County Virginia Deeds, Vol. One 1749-1755 (Washington, D.C., 1975), p. 20.

18. Ibid., p. 23.

19. Ibid., p. 14.

20. Ibid., p. 20.

21. Ibid., p. 41.

22. John Frederick Dorman, compiler Culpeper County. Virginia, Will Book A, 1749-1770 (Washington, D.C., 1956), pp. 96-97. Francis Cooper may have been unable to write since he signed his mark when he was a witness for the probate of the Scott will in 1764.

23. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, Washington, D.C., application filed February 25, 1833, at Saline County, Missouri by Benjamin A Cooper. Pension record S 16722. Cooper reported he was born January 25, 1756 in Culpeper County, Virginia. Alice Kinyon Houts, editor, Revolutionary Soldiers Buried in Missouri (Kansas City, 1966), p. 59 uses the date January 25, 1753 but adds 1756 parenthetically. Dorothy Ford Wulfeck, Marriages of Some Virginia Residents. 1607-1800, Vol. I (Baltimore, 1986), p. 148, relying on Daughters of the American Revolution records (DAR No. 47-226) uses the 1756 date. Benjamin Cooper later played a prominent role on the frontier in Kentucky and Missouri.

In an 1889 interview with frontier historian Lyman Draper, Stephen Cooper, a son of Sarshel and grandson of Francis, called his grandfather “Frank”, (Draper MSS 11 C 98). The surviving eighteenth century records, all of them official documents, uniformly use Francis.

Historians of the frontier are deeply in debt to the energy and foresight of Lyman Copeland Draper (1815-1891). Draper became interested in the history of the Trans-Allegheny West as a college student and devoted most of his adult life to collecting documents and interviewing pioneers and their descendants. The 500 volume Draper collection of records, letters and field notes of 1200 interviews are at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin in Madison, where Draper served as Secretary for 32 years. The Draper manuscript collection is also available on microfilm at other research libraries. JosephineL Harper, Guide _tQ the Draper Manuscripts (Madison, Wisconsin, 1983).

24. Militia rosters in Henings Statutes at Large in William Armstrong Crozier, editor, Virginia Colonial Militia (New York, 1905), p. 58. A grandson of Francis Cooper recalled in 1868 that the Coopers were related to the Russell’s of Culpeper County. He believed that his grandmother Cooper had been a Russell. Joseph Cooper, Draper MSS 23S137.

25. Lloyd DeWitt Bockstruck, Viq�inia’s Colonial Soldiers (Baltimore, 1988), p. 162, from the Journal of the House of Burgesses. Capt. Brown served 95 days and Lt. Col. Russell served 16 days. It is unlikely that the Culpeper militia engaged in combat during the spring of 1756.

26. John Frederick Dorman, editor, Culpeper County. Virginia Deeds, Volume Two, 1755-1762,

p. 64. The 1761 transaction is recorded in Deed Book C, pp. 489-491.

27. The birth date of Sarshel Cooper was reported by Joseph Cooper in Draper MSS 23S124 and the death by Stephen Cooper in Draper MSS 11Cl 04 and Mary E. Cavanaugh in Draper MSS 23S251 (see also Chapter 4 of Part II below.) Jesse Morrison reported that there were four Cooper brothers in Missouri in Draper MSS 30C89. (Morrison included Braxton Cooper, a younger brother of Benjamin and Sarshel.) Stephen Cooper described Betty Cooper Wood in Draper MSS 11C101 and mentioned that there were several children in Draper MSS 11C98.

28. Schell, Culpeper History. p. 37. During this period Colonel Richard Tutt, a St. Mark’s Parish neighbor of Francis Cooper owned more than 3000 acres in Culpeper County.

29. Samuel Eliot Morrison, editor, The Parkman Reader (Boston, 1955), p. 281, as quoted in Francis Parkman’s LaSalle and the Discovery of the Great West, originally published 1869.

30. Morrison, Parkman Reader, pp. 360-433. The “Sack of Deerfield” and two chapters on the siege and capture of Louisbourg are from Parkman’s A Half Century of Conflict, originally published 1892. The fort at Louisbourg was returned to the French as part of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ending the war.

31. George Washington letter of July 8, 1755 to Robert Dinwiddie in Ralph K. Andrist, editor, George Washington (New York, 1972), p. 56.

32. James Innes letter of July 11, 1755 to “all whom this may concern” in Freeman, George Washington Vol. II, pp. 84-85.

33. Hayes Baker-Crothers, Virginia and the French and Indian War (Chicago, 1928), pp. 82-100 and Freeman, George Washington, Vol. II, pp. 106-114. After 1705, the resident Governor of Virginia had the official title lieutenant governor.

34. Ibid., Vol. II, pp. 115-168.

35. Robert Dinwiddie letter of August 20, 1755 to John Spotswood in Schell, Culpeper History.

p. 33.

36. George Washington letter of April 1756 to Thomas Lord Fairfax, Ibid.

37. Freeman, George Washington, Vol. II, p. 174.

38. George Washington letter of April 27, 1756 to Robert Dinwiddie, Ibid., p. 182.

39. Ibid., pp. 171-174.

40. George Washington letter of May 9, 1756 to Robert Dinwiddie in Schell, Culpeper History.

p. 33.

41. Freeman, George Washington, Vol. II, p. 185.

42. Ibid., p. 187.

43. Ibid., p. 192.

44. Robinson, Southern Colonial Frontier, pp. 215-217.

45. Schell, Culpeper History. p. 34.

46. Great Britain declared war May 17, 1756. News of the declaration reached Williamsburg August 7 and the Virginia frontier August 15. Freeman, George Washington, Vol. II, pp. 204-205.

47. Morrison, Parkman Reader, p. 482, from Parkman’s Montcalm and Wolfe, originally published 1884.

48. Dale Van Every, Forth to the Wilderness, (New York, 1961) pp. 94-98.

49. Baker-Crothers, Viq�inia and the French and Indian War, p. 157.

50. W. Keith Kavenagh, editor, Foundations of Colonial America: A Documentary History. (New York, 1973), pp. 2340-2344.

51. George Washington letter of September 21, 1767 to William Crawford in Freeman, George Washington, Vol. III, p. 189.

52. Ibid., p. 190.

53. Van Every, Forth to the Wilderness, pp. 276-286.

CHAPTER TWO

THE FRONTIER BEFORE THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR, 1763-1775

Europe extends to the Alleghanies; America lies beyond.

Ralph Waldo Emerson1

During the first 150 years of the colonial period, settlements had remained clustered along the Atlantic seacoast, the coastal plains and the navigable rivers. During this period, the frontier advanced westward at a rate of approximately one mile a year as newcomers, some of them immigrants, and some young adults crowded out of the farms and towns where they had been raised, cleared land and established farms on the edge of settled areas. This incremental advance was deflected by physical barriers or by Indian claims but was generally westward toward the 1300 mile long mountain range on the horizon. In the middle of the eighteenth century, the rate of advance suddenly accelerated as the pioneers flowed down the Valley of Virginia and surged through the mountains on the roads to Pittsburgh constructed by Braddock and Forbes. Although the royal proclamation of 1763 prohibited settlement beyond the mountains, the pioneers were poised to leap the barriers and move west.

Early Settlement in Tennessee

The wilderness over the mountains from North Carolina which later became Tennessee was first explored by Europeans in 1540 during Hernando de Soto’s expedition through the southeast. By 1740, Tennessee was visited regularly by long hunters and Indian traders from Virginia and North Carolina. As late as 1768, a traveler described what is now northeastern Tennessee as “nothing but a howling wilderness.”2 On his return through the same area in 1769, the traveler found pioneers clearing land and building cabins. William Bean, with others from Pittsylvania County, Virginia, were locating on the Watauga River, a tributary of the Holston, in the comer of Tennessee near the Virginia-North Carolina boundary. The 1769 settlement at Watauga was west of the 1763 Proclamation Line but was in a small area that the Cherokee ceded to the British as part of the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber. Within the next few years, hundreds of people from Virginia and North Carolina were moving to Watauga. Some of these were Regulators from the Piedmont region of North Carolina whose armed protest against the colonial government had been crushed at the Battle of Alamance in May 1771.3

During 1770 and 1771, pioneers from Virginia and North Carolina established four tiny communities in the mountain valleys at the southwest comer of Virginia. The Watauga settlement was around Sycamore Shoals, present-day Elizabethton, Tennessee. In 1770, Evan Shelby built a station at Sapling Grove on the North Holston near present-day Bristol along the Tennessee-Virginia border. John Carter settled at Carter’s Valley, immediately west of the Holston, while Jacob Brown established a fourth community south of Watauga on the Nolichucky River in 1771. The Watauga settlers had believed that they were locating in Virginia and expected to “hold their lands by their improvements as first settlers.”4

When a 1771 survey found that all the Watauga settlements except North Holston were outside Virginia on Indian land, the Wataugans were,

…disappointed and being too inconveniently situated to remove back and feeling an unwillingness to loose the labor bestowed on their plantations they applied to the Cherokee Indians and leased the land for a term of ten years.5

In 1772, the settlers adopted Written Articles of Association in which they established procedures for self-government. These written articles have not survived but the Watauga Association of 1772, on the remote frontier, was the first independent government established by the governed in North “‘ America.6 By 1774, the settlements on the Virginia-Tennessee-North Carolina border were able to raise four militia companies to march to the Ohio River as part of the army assembled in Lord Dunmore’s War.7

The following year, although the Royal Proclamation remained in effect, settlers and land speculators intensified their efforts to secure land claims across the mountains. Judge Richard Henderson of North Carolina formed the Transylvania Land Company and negotiated to purchase land from the Cherokee. In the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals, Henderson paid 10,000 pounds to acquire a huge parcel of land reaching to the Ohio River and including much of what is now central Kentucky and north-central Tennessee. With the Cherokee in a mood to sell, the Watauga settlers bought the land they had leased since 1772. The Watauga purchase, completed March 19, 1775, included 2,000 square miles of land on the Watauga and New Rivers. A few days later, Jacob Brown bought a parcel of land, nearly as large as the Watauga purchase, along the Nolichucky River.8 Not all the Cherokee shared the enthusiasm for land sales. According to legend, Dragging Canoe, the son of a respected Cherokee chief, ominously described the area purchased as a “dark and bloody” land.9

Early Settlement in Kentucky

In the Spring of 1750, Thomas Walker, a physician and surveyor, and five companions traveled from their Virginia homes into the wilderness that would later be called Kentucky. Walker and his party, following the route that the Kentucky pioneers would use a quarter century later, crossed the gap in the Appalachian Mountains they named for the Duke of Cumberland. The party also named a river for the Duke and erected a small cabin, the first in Kentucky, at a location they called “Walker’s Settlement.” Ambrose Powell, a member of the Walker party and later surveyor of Culpeper County, Virginia, left his own name on one of the rivers they crossed. Walker’s party retraced their route and returned to their Virginia homes in July 1750.10

Long hunters from Virginia and North Carolina began to visit Kentucky on extended hunting expeditions beginning in the mid 1760’s. Daniel Boone (1734-1820) settled first on the Yadkin River frontier of North Carolina. In 1760-1762, when Indian attacks made the Yadkin untenable, Boone moved to Culpeper County, Virginia where he lived for two years and found work driving tobacco wagons.11 In May 1769, Boone led a party of five long hunters through Cumberland Gap into Kentucky in May 1769. The hunting party, with some changes in personnel, remained in Kentucky two years despite being captured twice by Indians. When Richard Henderson negotiated the purchase of Kentucky as a part of the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals in March 1775, he immediately engaged Boone to hire a company of men to build a road over the mountains to Kentucky. By early April, Boone and thirty men had blazed the narrow foot trail 200 miles over Cumberland Gap to the Kentucky River where they built Fort Boonesborough. Boone’s Trace of 1775, with minor variations, became the Wilderness Road followed by emigrants to Kentucky for twenty years.

Lord Dunmore’s War

By the early 1770s, the conflicts between Indians and settlers had intensified on the wilderness frontier that Virginia and neighboring colonies claimed. A growing population in the settled areas of Pennsylvania, Virginia and North Carolina was pressing against the natural barriers of the Appalachian mountains and jeopardizing political agreements with the Indians. The fundamental conflict was between the settlers who saw wilderness as something to be cleared and cultivated and the Indians who saw wilderness as something to be left undisturbed. In this early environmental conflict, the developers were pitted against the preservationists.

The interests of the settlers in new and cheap western lands coincided with the interests of powerful land speculators, including patriots like Benjamin Franklin and George Washington as well as British officials like Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia. The Indian interest in keeping the wilderness undisturbed coincided with the interests of trappers, traders and British policies to protect the Indians and prevent the formation of coalitions against the British. The Proclamation Line of 1763 and several subsequent boundaries had proven ineffective in restraining the settlers or protecting western lands for the Indians and the Crown.

John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore Viscount Fincastle, Baron Murray of Blair, of Monlin, and of Tillimet (1732-1809), was appointed governor of Virginia by the king in 1771. Lord Dunmore quickly recognized the independent spirit of the colonial pioneer. As he later wrote to his superiors in London:

I have learnt from experience that the established authority of any government in America, and the policy of Government at home, are both insufficient to restrain the Americans; and that they do and will remove as their avidity and restlessness excite them. They acquire no attachment to Place; But wandering about Seems engrafted in their Nature;…they do not conceive that Government has any right to forbid their taking possession of a Vast tract of a country either uninhabited or which Serves only as a Shelter to a few Scattered Tribes of Indians. Nor can they be easily brought to entertain any belief of the permanent obligations of Treaties made with those People, whom they consider as but little removed from the brute Creation.12

Apart from his private interests as a land speculator, Lord Dunmore was also responsible for maintaining British authority in the midst of the fractious and energetic colonists. In addition, he wanted to protect the land in the West that Virginia claimed from the competing claims of other colonies including Pennsylvania and North Carolina.

The Shawnee had once lived along the Cumberland River in Kentucky. After their conquest by the Iroquois, the Shawnee moved north across the Ohio River to the Scioto Valley where they built towns. Although they lived in what is now Ohio, the Shawnee continued to hunt in the wilds of Kentucky where they encountered growing indications of exploration and settlement. Fierce and proud, the Shawnee had been infuriated by the arrogance of the Iroquois who, to protect their own lands, had sold lands occupied and used by the Shawnee as part of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. The Shawnee attempted to persuade other tribes to join them in attacking the settlements. Only the Mingo, an Iroquois band living in Ohio, shared the Shawnee vision of a confederated Indian campaign to enforce treaty rights.13

While the reluctance of the Indians to unify allowed the settlements to spread, conflict was inevitable. The Indians trying to maintain their traditional rights and the settlers trying to expand their claims were on a collision course as they had been since the 1622 attacks on the settlers on the James River of Virginia and as they would be for another century until the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890. In response to increasing incidents between Indians and colonists, Lord Dunmore appointed John Connolly, Captain of the Virginia militia. In April 1774, Connolly responded to the murder of some traders in Indian territory with an open letter warning that the Indians were on the warpath.14 Needing little encouragement, the settlers responded with unprovoked attacks on Indians.

By June 1774, Lord Dunmore had concluded that the situation on the Virginia frontier was deteriorating and that an organized military campaign would be necessary. In a letter to his country lieutenants calling out the militia, Lord Dunmore reported,

…hopes of a pacification can be no longer entertained, and that these People will by no means be diverted from their design of falling upon the back parts of this Country and Committing all the outrages and devastations which will be in their power to effect.15

Dunmore notified the militia leaders to mobilize their troops for local defense or to advance with other units, suggesting the strategic potential of a fort on the Ohio River at the mouth of the Kanawha River. Dunmore also advised that it might be useful to erect small forts on the frontier to protect the settlers while the main body of militia was campaigning elsewhere.

John Connolly quickly issued another proclamation inflaming passions,

…the Shawanese have perpetrated several murders upon the inhabitants of this county which has involved this promising settlement in the most calamatous distress.16

Needing little provocation, the settlers went on the warpath. They attacked Indians wherever they encountered them including the brutal massacre of the family of the friendly and peaceful Mingo Chief John Logan. The patient Logan, severely provoked, retaliated, explaining in an eloquent letter,

What did you kill my people on Yellow Creek for. The white People killed my kin at Coneestoga a great while ago, & I thought [nothing of that.] But you killed my kin again…then I thought I must kill too…the Indians is not Angry only myself.17

But the conflict was much larger than Logan and his personal revenge.

On July 12, Lord Dunmore ordered Andrew Lewis (1720-1781), the militia commander to call out volunteers for a campaign against the Ohio Indians,

…by no means to wait any longer for them to Attack you, but to raise all the Men you think willing and Able, & go down immediately to the mouth of the great Kanhaway and there build a Fort, and if you think you have forse enough (that are willing to follow you) to proceed directly to their Towns & if possible destroy their Towns & Magazines and distress them in every other way that is possible.18

Lewis assembled three Virginia regiments and four independent companies at “The Big Levels of the Greenbriar” where the Virginians built Fort Union at the site of present-day Lewisburg, West Virginia. In addition to troops from the settled areas of Virginia, Lewis’ command included militia companies from the settlements on the Virginia-Tennessee border under the command of Evan Shelby (1750-1826) and William Russell (1748-1794).19 Lewis marched his army 140 miles to Point Pleasant, at the confluence of the Kanawha River and the Ohio River in what is now Mason County, West Virginia. Lord Dunmore ordered Colonel Lewis to build a fort at Point Pleasant where he would be joined by Virginia troops under Dunmore’s personal command. The combined army would then invade Ohio and attack the Shawnee towns.

While the local militia was marching toward Point Pleasant on the Ohio River, Indians were continuing to threaten the frontier settlements of Southwestern Virginia. William Russell wrote in July that the Clinch River settlers had built three forts but were short of supplies:

The Ammunition is so bad, that the Inhabitants in the Different Forts slam easily about it, whether they have it by them or not to make Defence, and they are Intirely without, and we have only fifty bit of head with the Podder…20

Within weeks, the frontiersmen had built a string of seven small forts in Fincastle County to protect the settlements on the Clinch, Holston and New Rivers of southwestern Virginia against Indian raids. By early September, when Indians attacked outlying frontier settlements, Maj. Arthur Campbell reported “the Forts at Glade-Hollow, Elk-Garden and Maiden Spring, has their compliments compleat.”21 These forts were under the overall command of Lt. Daniel Boone.

Francis Cooper, who had served in the Culpeper County militia during the French and Indian War, enlisted in September 1774 in Lord Dunmore’s War. Along with Abraham Cooper, Archibald Scott and James Scott, Francis Cooper was among twenty privates who served under Ensign Hendly Moore at Glade Hollow Fort during September 1774.22 Indians raided the frontier settlements during September killing or capturing members of two families and destroying livestock. The troops in the forts pursued the raiders but were unable to recover any of the captives. Despite a chronic shortage of ammunition, the militia successfully held the frontier settlements during Lord Dunmore’s War. The militia served in the forts until the end of the war and the return of the Fincastle County militia.23

By the time Colonel Lewis and his army arrived at Point Pleasant on the Ohio River, Cornstalk, the Shawnee Chief, had assembled a confederated army of approximately 1200 warriors. In addition to Shawnee, Chief Cornstalk was accompanied by braves from the Mingo, Wyandot, Ottawa and other tribes. During the night of October 9, Cornstalk and his warriors rafted across the Ohio River several miles upstream and approached the Virginia encampment. The Indians were sneaking up on the Virginia camp when they were discovered by hunters sent out by ttie colonial troops. The hunters were able to alert the Virginians to form battle lines before Cornstalk and his warriors attacked.24 One of the participants described the battle:

…a hot engagement Ensued which Lasted three hours Very doubtful the Enemy being much Suppirour in Number to the first Detachments Disputed the ground with the Greatest Obstinacey often Runing up to the Very Muzels of our Gunes where the[y] as often fell Victims to thire Rage…25

Without the advantage of surprise, terrain or fortifications, the battle was one of very few in which two groups of wilderness warriors, in this case colonial settlers and Ohio Indians, were evenly matched. The battle raged most of the day with heavy losses on each side. Col. William Fleming (1729-1795), the commanding officer of the Botetourt County militia was severely wounded at Point Pleasant. He reported,

We had 7 or 800 Warriors to deal with. Never did Indians stick closer to it, nor behave bolder, the Engagement lasted from half an hour after [sunrise] to the same time before sunset. And let me add I believe the Indians never had such a scourging from the English before. they scalped many of their own dead to prevent their falling into Our hands…we tooke 18 or 20 scalps, the most of them principle Warriors amongst the Shawnese…26

Late in the day, the Virginia troops attempted a flanking maneuver. The Indians noticed the troop movement but mistakenly interpreted it as the arrival of reinforcements and withdrew from the battle.

Writing from the battlefield, a young Isaac Shelby respectfully described the turning point in the day-long battle and the stubborn resistance of the Indians,

The enemy, no longer able to maintain their ground was forced to give way…the action continued extremely hot, the close underwood, many steep banks and logs greatly favored their retreat, and the bravest of their men made the best use of themselves…Their long retreat gave them a most advantageous spot of ground…27

Many of the participants who wrote about the battle mentioned the bravery of the Indian warriors and, as if it were routine, admitted that the Virginians had scalped the Indians they killed. Capt. William Myles recounted,

I cannot describe the bravery of the enemy in battle…Their Chiefs ran continually along the line exhorting the men to “lye close” and “shoot well”, “fight and be strong”…they fought desperately, I believe, and retreated in such a manner as to carry off all their wounded…28

Capt. John Floyd, already a pioneer in Kentucky, wrote, about the Indians,

…they were obliged to give Ground which the[y] Disputed inch by inch till at Length the[y] Posted themselves on an Advantagus piese of Ground Where the[y] Continued at Shooting now and then until night putt an End to that Tragical Seen and left many a brave fellow Waltirring in his Gore…[our] loss of men is very considerable…29

By the end of the day, 75 Virginia colonists had been killed and 140 wounded in the Battle of Point Pleasant.30

Although the battle was a draw with neither side gaining advantage, the Indians withdrew to Ohio and began peace negotiations. Lord Dunmore, arriving after the only battle in the war that bears his name, marched his troops into Ohio and ordered Colonel Lewis to release the veterans of Point Pleasant to return to their homes. In the Treaty of Camp Charlotte, the Shawnee promised Lord Dunmore that they would cease all hunting east of the Ohio River, stop attacks on Ohio River boats and obey Royal proclamations. The Indians had held their own in the Battle of Point Pleasant but lost their traditional hunting grounds in the treaty that concluded Lord Dunmore’s War.31